Museum Exhibition Dates: September 22, 2023 - January 6, 2024

Twenty-five Artworks cannot tell a complete story...

|

However, they do provide a glimpse into the vital roles Anishinaabe, Inuit, and Pueblo women have always fulfilled in their families, communities, the art world, and beyond. Spanning 125 years, from 1895-2021, this exhibition celebrates some of the critical roles Anishinaabe, Inuit, and Pueblo women fulfill in their families, their communities, the art world, and beyond. Rooted in contemporary and historical artworks, this traveling exhibition explores themes like mothering, making, art world success, spirituality, and continuity in visual culture across generations.

Spotlight Anishinaabe, Inuit, and Pueblo women artists include: Kenojuak Ashevak (Inuit), Kelly Church (Gun Lake Band of Pottawatomi/Grand Traverse Ottawa/Chippewa descent), Maria Martinez (San Ildefonso), and many more. Vitality and Continuity: Art in the Experiences of Anishinaabe, Inuit, and Pueblo Women is organized by the Detroit Institute of Arts, Bonifas Arts Center, Dennos Museum Center, Midland Center for the Arts, and the Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum. This exhibition is one in a series of American art exhibitions created through a multi-year, multi-institutional partnership formed by the Detroit Institute of Arts as part of the Art Bridges Initiative. |

Norval Morriseau, Cycles, ca. 1985

|

Taking care of

A woman works at home with a child on her back...

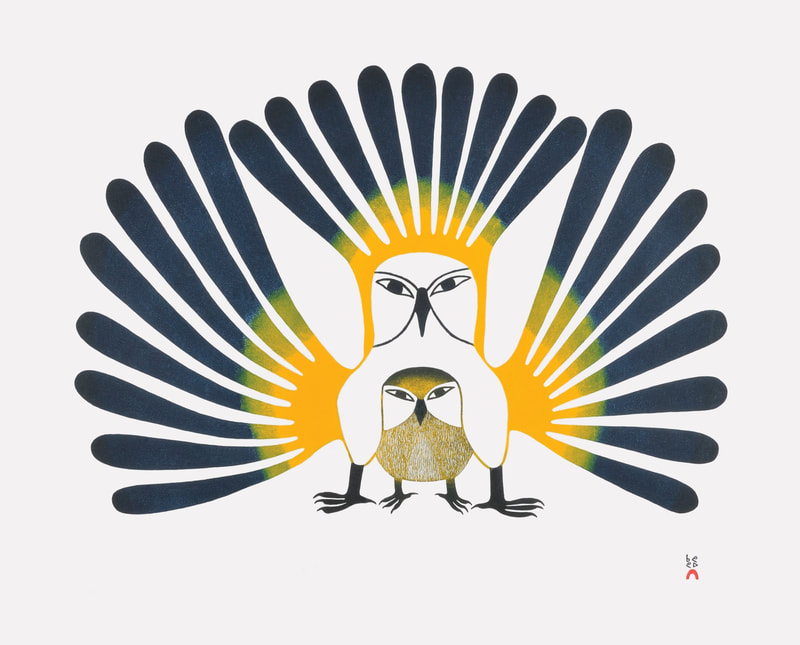

Outside, another does laundry at the lake...

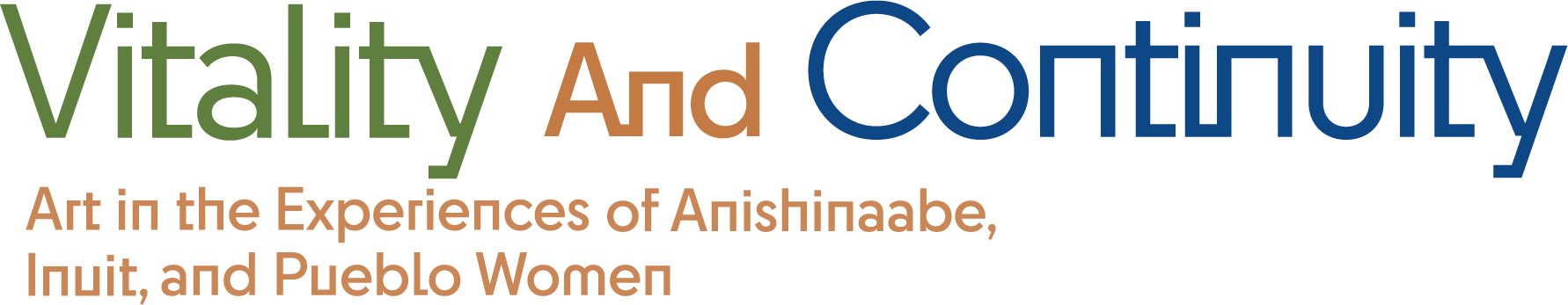

A young owl, with its juvenile brown coat, is nestled between its mother's legs...

The works in this section explore how Inuit and Anishinaabe women care for their children, their families, their homes, and their environment. Despite pressure from colonizers to adopt Western methods of childrearing, education, and environmental stewardship, these ways of caring persist.

Outside, another does laundry at the lake...

A young owl, with its juvenile brown coat, is nestled between its mother's legs...

The works in this section explore how Inuit and Anishinaabe women care for their children, their families, their homes, and their environment. Despite pressure from colonizers to adopt Western methods of childrearing, education, and environmental stewardship, these ways of caring persist.

|

Pitaloosie Saila

Mother with Ulu Etching and Aquatint on Paper 1996 |

Pitaloosie Saila

The Red Mitts Lithograph on Paper 2002 |

Kenojuak Ashevak

The Sun's Return Stone Cut and Stencil 1993 |

|

"To us, Lake Superior is alive, not in a simple, superstitious sense as depicted in stereotypes of Native people, but in a truly scientific way."

-Lois Beardslee Throughout her painting, Beardslee uses stylized visual shorthand that has been preserved and adapted through generations to embed deep knowledge of Ojibwe land and lifeways.

Lois Beardslee Potty Training, Dixon Island, Lake Superior, 2001 Acrylic paint, black water-proof gel pen, hand-made paper |

Spirituality in ArtThe art in this section includes symbols, stories, and images related to the artists' spiritual beliefs and experiences. As you explore, consider the relationships between belief systems that come from within Anishinaabe, Inuit, and Pueblo communities and Christianity, a religion introduced through colonization.

Look for:

Norval Morisseau Cycles Acrylic Paint on Canvas About 1985 |

|

Norval Morrisseau

Visionary Wife and Child Acrylic on Board 1974 |

Kenojuak Ashevak

Quviashutuq Arnaq/Happy Woman Lithograph on Paper 2000 |

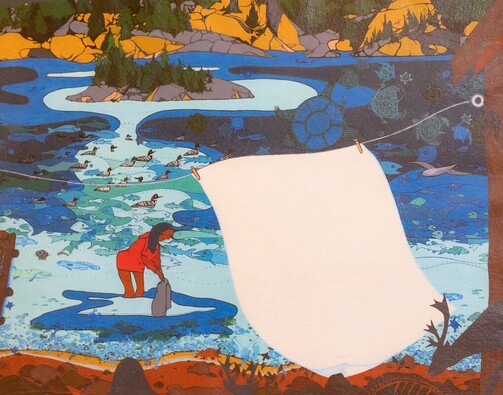

Pitaloosie Saila

Strange Ladies Lithograph on Paper 2006 |

Church run boarding schoolsStarting in the 1800s, the United States and Canadian governments mandated boarding schools, and churches ran many of them. Their purpose was cultural genocide; the eradication of Native American languages, traditions, and religions.

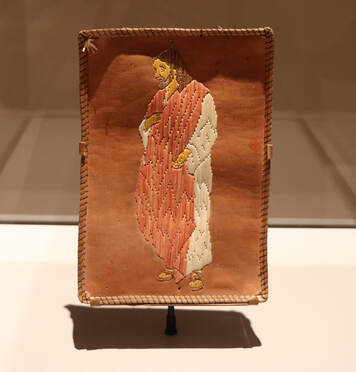

Government agents abducted children from their parents and placed them in boarding schools, where they were forced to adopt Euro-American culture-including Christianity. The children suffered emotional, mental, physical, and sexual abuse, and many were murdered. Indigenous resistance and resilience caused this genocide to fail. But the trauma of state-authorized boarding schools continues to impact generations of Native Americans today. Unknown Artist Birch Bark and Quill Plaque or Book Cover About 1935 |

art speaks through time

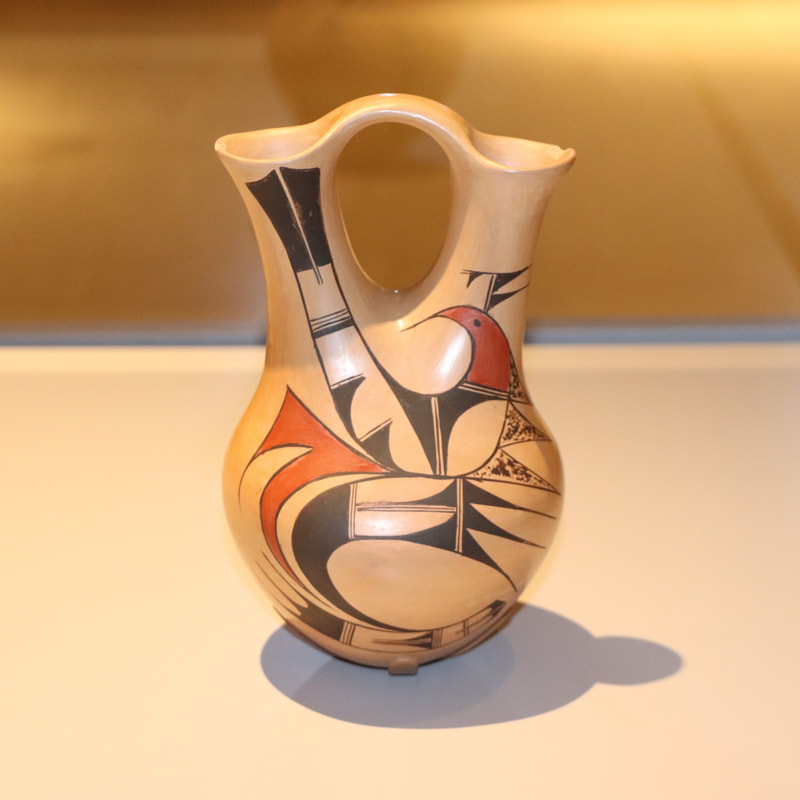

Anishinaabe and Hopi artists continue to expand on the visual culture that preceded them, while responding to the social, political, and environmental influences of their time. Often given as gifts, works like these demonstrates how:

- The disappearance of black ash trees impacts a weaver's baskets.

- A bird travels across generations from a bowl to a vase.

- An artist responds to a new demand for knitting accessories using familiar materials like birch bark and porcupine quills.

|

Unidentified Artist

Knitting Basket Birch bark, Braided sweetgrass, Dyed porcupine quills. Mid-1900s |

Nyla Sahmie Nampeyo

Hopi Wedding Vase Clay 1970-80 |

Kelly Church

Vinyl Basket Vinyl, Black Ash Strip 2021 |