MARSHALL FREDERICKS ONLINE EXHIBITIONS

January 20th-May 4th, 2024

TEACHER'S GUIDE NOW AVAILABLE!

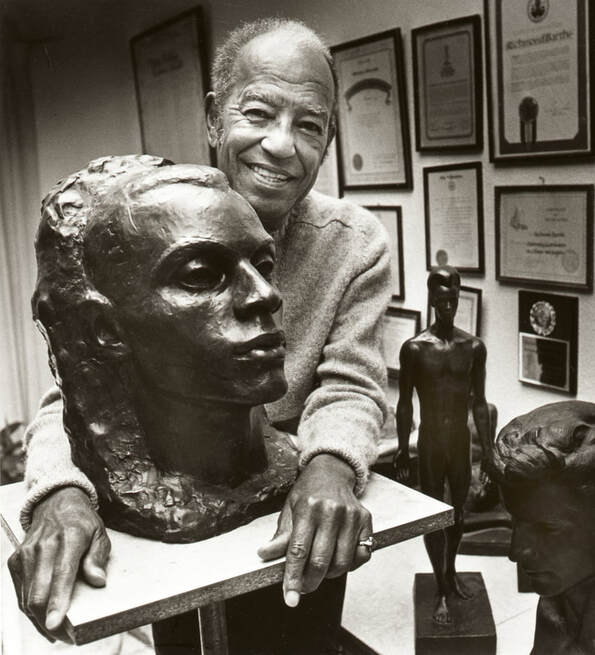

Richmond Barthé - (1901-1989)

|

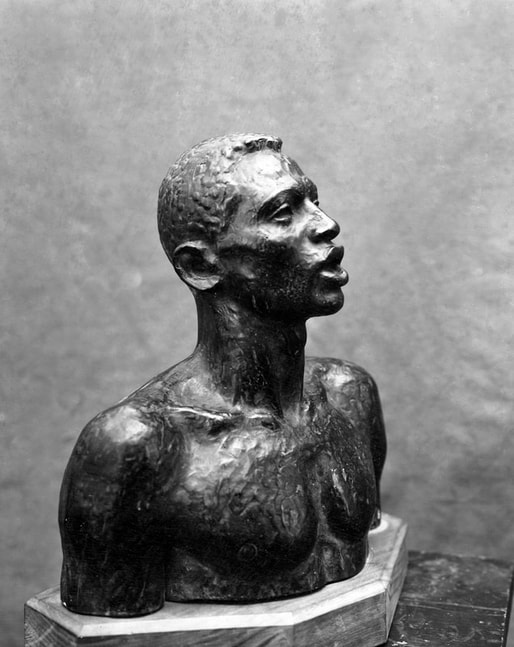

Harlem Renaissance sculptor Richmond Barthé (1901—1989) is recognized as one of the foremost sculptors of his generation. This exhibition, curated by esteemed art historian, Samella Lewis, Ph.D., in conjunction with the publication of her extensive biography Barthé, His Life in Art, provides a rare opportunity to admire over 20 of his most elegant and important crafted bronze creations that depict dancers, workers, religious figures, and icons in Black History like singer Josephine Baker and actor Paul Robeson. His masterful sculptures celebrated Black identity, portraying the beauty, dignity, and humanity of African American subjects at a time when their representation was scarce in the art world. Barthé's works challenged societal norms and stereotypes, offering a counter-narrative through his profound artistic expression. Through his art, Barthé not only captured the essence of Black life and culture but also paved the way for greater recognition and acceptance of African American artists within the broader artistic community, leaving an enduring legacy that continues to inspire.

|

Artist Influences

|

James Richmond Barthé was born in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, 1901. Shortly after his birth, when he was only a month old, his father died at age twenty-two. Never really knowing his father, Barthé’s mother was the artist’s first encourager of the young boy’s love of the arts. Barthé recalled that his mother often gave him his favorite toys—a marking pencil/crayon and paper—to entertain him during her busy periods while she worked.

As a child he was fascinated with shapes, especially those of fancy old English letters that he saw in the headlines of the New Orleans Times Picayune. He also enjoyed comic strip characters. At the age of twelve, his work was shown at a county fair in Mississippi. By the age of eighteen, Barthé, now residing in New Orleans, won his first prize—a blue ribbon for a drawing he sent to the county fair. His work attracted the attention of Lyle Saxon, the literary critic (who was also interested in art) of the New Orleans Times Picayune. Saxon tried, unsuccessfully, to register Barthé in a New Orleans art school. The refusal was based on Barthé's race, rather than a lack of creative ability. This only encouraged Barthé even more in pursuing an art career. With the aid of Reverend Harry Kane, Barthé, with less than a high school education and no formal training in art, was admitted to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1924. Reverend Kane provided tuition during Barthé’s four-year stay at the Institute as a painter. Fortunately, the artist was able to live with an aunt who agreed to provide free housing while he was studying in Chicago. During the last year of his study at the Art Institute, Barthé's anatomy teacher, Charles Schroeder, suggested sculpting in clay. Barthé stated, "a fellow student had a beautiful head. I wanted to get it in three dimensions instead of the single dimension of painting, so I asked him if I could model his head. I have always done sculpture since then." As the proverbial saying goes, the rest was history. |

The Harlem Renaissance

|

In America during the 1920s and 1930s, thousands of African Americans migrated from the rural agricultural South to the urban, industrialized North, fleeing racial and economic oppression and seeking racial and economic opportunity. Dr. Alain Locke (1886–1954), a writer, philosopher, and patron of the arts, and an intellectual leader of the Harlem Renaissance, was the seminal force behind “The New Negro Movement,” later referred to as the Harlem Renaissance.

The Harlem Renaissance was a Black cultural movement of creative activity using art, literature, music, dance, and social commentary. This movement encouraged African Americans to become politically progressive and racially conscious. Locke encouraged black artists to seek their artistic roots in the traditional arts of Africa rather that the art of white America or Europe. Other well-known visual artists of the Harlem Renaissance include Aaron Douglas (1898-1979), Augusta Savage (1892-1962), musicians such as Duke Ellington, novelists such as Jean Toomer, and poets such as Langston Hughes. In 1929, after graduating from the Art Institute in Chicago, Barthé moved to Harlem NY during the height of the “Harlem Renaissance” and established his first studio and began to fraternize with writers, dancers and theater personalities soon after he arrived. His reputation as a sculptor grew and was generally known in Harlem and acclaimed by Locke, who praised his sculpture and regarded it as fresh and vibrant. Click here to access a Harlem Renaissance music playlist |

Male Figures

|

Richmond Barthé is best known for his portrayal of Black figures. Much of the focus of his artistic work was portraying the diversity and spirituality of man. During his life, Barthé made several comments on his work that gives viewers insight to the content of his sculptures.

“Ninety percent of my work is of Black people. I do my work to please myself, and if people like my pieces, they buy them. I suppose that's rather selfish, but it's what I have to do.” “I want to show the spiritual side of the Negro, his customs and his culture and to interpret these in a way that would bring about a better understanding between the races.” “I hope that my people will look into my works and see a reflection of themselves. I have been trying to hold up a mirror to them and say, ‘Look how beautiful you are.’ It wasn't until ‘yesterday’ that they suddenly realized that they were beautiful. My dream in life was to make my people proud of me and show them how beautiful the world is.” "All my life I have been interested in trying to capture the spiritual quality I see and feel in people, and I feel that the human figure as God made it, is the best means of expressing this spirit in man." (Adams, 1978) When Barthé moved to Harlem in 1929, he entered an established network of gay men and women. Although he was described as closeted all his life, it was said by Margaret R. Vendryes, his biographer, that, “he didn’t leave a silenced legacy. Look a bit closer at his art. The real story is there for the taking.” Many of Barthe’s sculptures display a characteristic that can be considered homoerotic and/or androgynous. These include works such as Stevedore and Feral Benga both of which can be viewed in this exhibition. |

Barthé's Creative Process and Philosophy

“Man is like a light bulb. It can only get light through the little wire that connects it directly with the power plant. So, it has to go within itself for light. Man, like the light bulb, is connected to the universal mind, cosmic consciousness or God—whatever you want to call it—and the only way he can get help or inspiration is by going within himself and drawing on this power. This is where artists, poets, composers, and scientists get their ideas and inspiration. It is the source of all knowledge. You just have to go within, relax, and let it flow through you.” –Richmond Barthé

|

Richmond Barthé did not believe that race should determine what an artist should produce. He did, however, feel that his race was an advantage in his rise to fame. “Being a negro has been a help rather than a hindrance to me. In the Chicago Art Institute, my work was always noticed because I was the one negro in that particular section. I’m sure there were other students doing better work at the time who were not noticed. Art is not racial. For me there is no negro art—only art. I have not limited myself to negro subjects. It makes no difference in my approach to the subject matter whether I am to model a Scandinavian or an African dancer. For instance, I selected a young negro as my model for the marble head, ‘Jimmie,’ because of his particularly engaging smile. If he had been white and had the same smile, I’d have chosen him just as readily.”

“If I had my life to live over... I would be born a Negro at the Bay, same parents, same obstacles and the same amount of formal education. All my life I've been trying to capture the beauty that I see in people. I have done many portraits of White persons, but my chief interest is in the Negro. I [had planned] to spend a year and a half in Africa, studying types and making sketches and models, which I [wanted] to finish off in Paris for a show there and later in London and New York City. I want to do more than types, however.” |

Life and Legacy

|

By 1934, Barthé was awarded his first solo show at the Caz Delbo Galleries in New York City. His exhibitions and commissions were numerous and his works were being added to the permanent collections at many museums, including the Whitney Museum which acquired African Dancer, Blackberry Woman, and Comedian. The Metropolitan Museum of Art also added Barthé’s The Boxer to their museum collection.

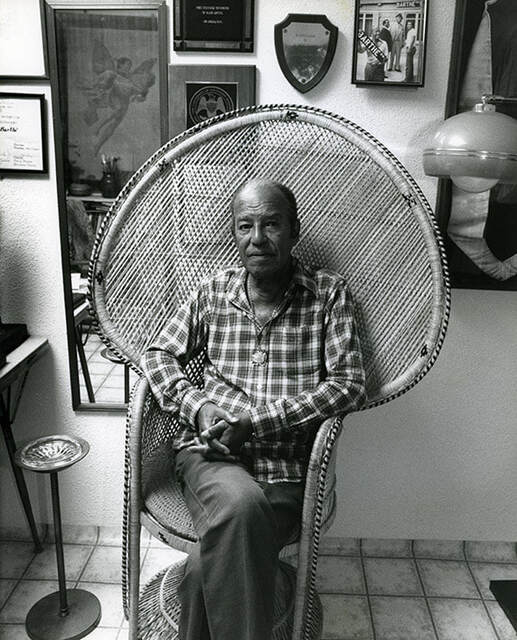

As his commissions grew, Barthé decided to move his studio from Harlem to a larger, more comfortable space downtown New York City. While living downtown, Barthé was able to attend the theater and dance performances. These experiences influenced his art and many famous performers became the subjects of his work. At what may have been the very peak of his career, Barthé made the decision to leave his life of fame and move to Jamaica where he remained for the next twenty years. It was in Jamaica, that Barthé’s struggles with his mental health became more prominent. At the time, he was diagnosed with depression and was hospitalized both in Jamaica and then back in New York. Following that, he was then diagnosed with schizophrenia. After this hospitalization, Barthé returned to Jamaica but ended up leaving in the mid-1960s. He then moved to Switzerland, Spain, and Italy, over the following years before once again experiencing symptoms causing him to struggle with his mental health. Penniless and continuing to experience symptoms from his mental health diagnosis, Barthé ended up settling in Pasadena, California, in 1976. |

His Later Years in Pasadena, California

|

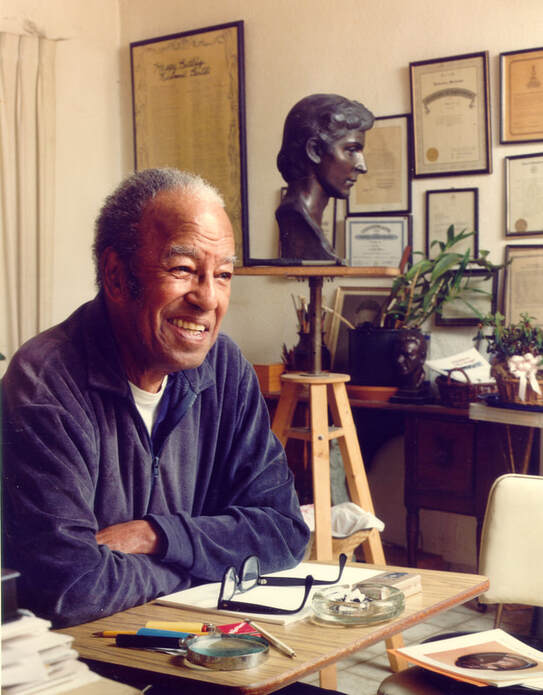

Artist Charles White and wife Fran found a small apartment for Barthé in Pasadena.

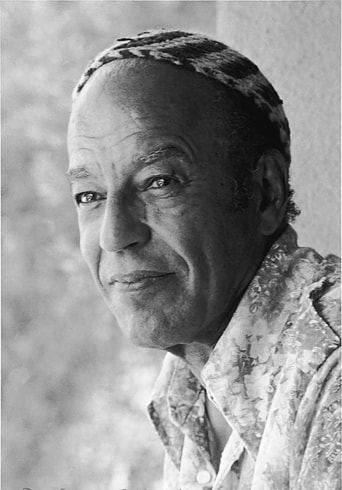

After establishing a friendship with Barthé, “The Rockford Files” actor, James Garner, became a generous source of income for the artist. Garner provided a stipend so that Barthé could meet his living expenses, which he offered kindly and graciously with the utmost dignity and consideration for the artist. Garner expected no repayment in the form of money or service. His wish was that Barthé, free of worrying about meeting monthly expenses could focus solely on creating art—all of which the artist could keep or sell at his own discretion. In addition, Garner hired a copyright attorney to assist Barthé in protecting and properly copyrighting his artwork so that it would not fall under the category of public domain. Garner also hired attorneys to set up a trust to protect the accounts of the artist and ensure that Barthé’s future would be secure. To oversee these activities, Garner established the Richmond Barthé Trust. Following the copyrighting of Barthé’s work, Garner funded the casting of editions of the artists sculptures, with Barthé designating the numbers in each edition. This was the first time that the sculptor had funds to make editions of his work. In essence, Garner provided some measure of protection for Barthé and became the sculptor’s "family". The actor then designated Dr. Samella Lewis to serve as Barthé's biographer and to collect, organize, and document his work. |

Richmond Barthé and Marshall Fredericks

|

Richmond Barthé and Marshall Fredericks were contemporaries, working both in the same time period and creating similar subject matter in their respective artworks oftentimes focusing on traditional figurative sculpture. In addition, both even produced some works classified by the Art Deco style such as Barthé’s Exodus and Dance wall relief (1938) at Kingsborough Houses in Harlem, New York, and Fredericks’s sculpture reliefs on the Horace Rackham Building in Detroit, Michigan (1941).

When you view Fredericks’s works in the Main Gallery of the Museum, style and subject matter connect to Barthé’s sculptures. Both artists focused on well-known personalities that they associated with and sometimes even knew during their lives. You will notice that both artists focused their subject matter based on their own racial make-up. With Barthé, most of the subjects in his sculptures were African American. The way he portrayed his subject matter was revolutionary at the time. He highlighted the essence of Black identity, showcasing the elegance, respect, and humanity of African American individuals during an era when their depiction was infrequently seen or caricatured within the art world. Both Fredericks and Barthé focused on the human figure in their work. In 1955, Fredericks’s created a credo for his artwork stating, “I love people, for I have learned through many experiences, both happy and sad, how beautiful and wonderful they can be. Therefore, I want more than anything in the world, to do sculpture which will have real meaning for other people, many people, and might in some way encourage, inspire, or give them happiness.” In a similar fashion, Barthé’s art reflected how he felt about whom and what he was studying. All his life, the artist said he had been interested in studying people. He loved people—people of all races, creeds, and economic levels. In exploring both their basic nature and their manifestation of that essence, he always tried to capture the spiritual quality inherent in them. Barthé said, "My work is not based on surfaces or stylization but on what is inside of it. I'm not interested in style, medium, or subject matter." |