organized by Bedford Gallery at the Lesher Center for the Arts, Walnut Creek, CA.

View the exhibition

|

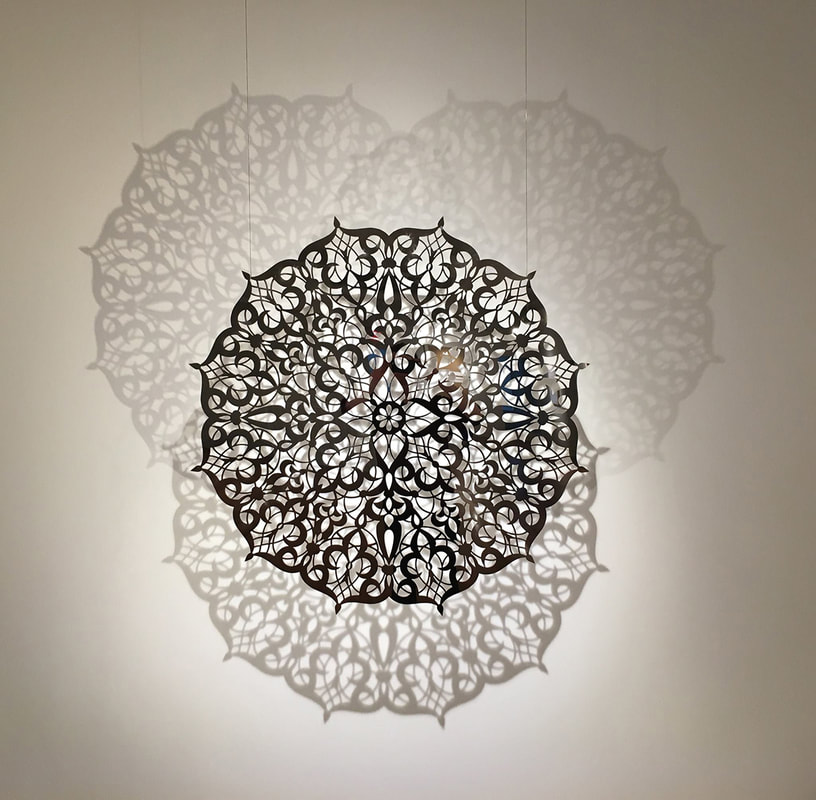

Anila Quayyum Agha

Teardrop (After Robert Irwin), 2016 Polished stainless steel with mirror finish, halogen light, edition 2/8 Courtesy of Talley Dunn Gallery, Dallas, TX Anila Quayyum Agha was born in Pakistan in 1965 and immigrated to the United States in her twenties. She currently resides in the mid-West and recently had a solo exhibition at the Toledo Museum of Art in 2020. In her art practice, Agha explores perceived cultural and social polarities such as masculine/feminine, public/private, religious/secular to address cultural identity, global politics, and gender roles. Her piece featured in Tradition Interrupted is from a series of metal artworks that imitate delicate embroidery or lacework to reflect these binary ideas. Agha’s Teardrop poetically reflects the plight and suspension of the refugee who is in motion but is restrained by many factors. Her use of light, reflection, and shadow allows viewers to contemplate the basic “black and white” ideas considered by many refugees: pain and peace, strength and struggle, life and death. Adorned with delicate geometric and floral cutouts found in ancient Islamic motifs, the steel form of Agha’s sculpture appears fragile but its material is resilient, hardy, and even stubborn in nature — very much like humans. Agha’s piece is also an homage to artist Robert Irwin’s suspended abstract disks, which were also pristinely illuminated. |

|

Faig Ahmed

Hal, 2016 Handmade woolen carpet, edition 2/3 Private collection Faig Ahmed is a master of illusion and is exceptionally skilled at transforming recognizable, comfortable, and formal symbols of his homeland into melted abstractions. Ahmed was born in Baku, Azerbaijan where he continues to live and work today. As a child, Ahmed began experimenting with dismantling Middle Eastern carpets. At the age of seven, his parents left him to play on a rug that was owned by his great-grandmother and, noting the range of patterns, his imagination ran wild. He found a pair of scissors and started cutting. He moved chunks of the rug into different positions until the heirloom was something completely new, and thus the inspiration for his future art career was born. Today, Ahmed uses computer technology to sketch lines and shapes that are woven into his signature rugs. Working with local weavers in Azerbaijan, Ahmed constructs the rugs using traditional, hand-woven methods and materials. The resulting work – a reinterpreted Middle Eastern rug that appears to be dripping or melting into a puddle – addresses complex ideas of identity, loss, and change. Ahmed is not simply interested in merging past and present; the internationally renowned artist remains focused on historic traditions as he states the past is “the most stable conception in our lives.” |

|

Camille Eskell

F-Ezra: Made a Woman, 2014 Digital imagery, felt, silk, mixed media, wood pedestal, platform Camille Eskell grew up in New York in the 1960s after her parents emigrated from Bombay, India. Both sides of her family manufactured and sold fez caps, a traditional Middle Eastern headpiece that now serves as a metaphoric blank canvas for Eskell. She constructs her stories from fabric, found objects, digital imagery, and sculptural elements while using a feminist lens to magnify underlying religious and cultural conventions. Eskell’s piece, F-Ezra: Made a Woman, addresses gender bias that is inherent in many religions and Old World cultures. The Hebrew excerpt that wraps around the front of the headpiece is from a morning blessing recited by devout Jewish men, giving thanks for not being “made a woman.” The women depicted are from the Ezra family (the central portrait is the artist's mother), set before the backdrop of their Bombay synagogue where females were relegated to the upstairs galleries. The veil and braid are suggestive of a harem girl, and the brass embellishments represent a kind of armor. Together, these elements suggest that women are expected to be strong, but hidden figures. |

|

Camille Eskell

Taskmaster Fez: Avadim (we were slaves), The Story of Joe, 2016 Digital imagery, felt, silk, mixed media, mirror, wood pedestal, platform Camille Eskell grew up in New York as the daughter of Iraqi Jewish parents who emigrated from India in the 1960s. As such, Eskell’s various cultural experiences inform her multifaceted work. Her piece, Taskmaster Fez: Avadim, we were slaves, (The Story of Joe) chronicles the effects of domination, control, and obedience through the interplay of two brothers: Eskell’s father, Joe, and his older brother Jack. Eskell depicts the transformation of Joe at the hands of the elder, Jack, who served as Joe’s father figure and employer after he immigrated to the United States. Built on a fez cap, the design references the hat of Egyptian taskmasters who were the overseers of slaves in Egypt. The images can be read from the left to right of the headpiece, where the change in demeanor and age of Joe characterizes the denigration of the once hopeful younger brother. The size difference in the men, with Jack pictured as the largest figure, assumes an ancient Egyptian stylistic tradition where the most powerful figure appears significantly larger in scale. The snake, also a traditional symbol in Egyptian art, signifies deceit and replaces the customary fez tassel. “Avadim” in Hebrew means “slaves,” and references a ritual prayer recited during the Jewish holiday, Passover, that begins with “Avadim Hayinu (we were slaves).” This personal, testimonial piece honors her father’s struggles and legacy while also recognizing the historic cultural underpinnings associated with contemporary societal expectations. |

|

Mounir Fatmi

Maximum Sensation, 2016 Skateboards, prayer rugs Mounir Fatmi was born in Tangier, Morocco in 1970 and has exhibited all over the world. Fatmi spent a good deal of his childhood at the flea market of Casabarata in Tangier where his mother sold children’s clothes. Surrounded by piles of everyday items at the market, Fatmi forged the beginnings of his conceptual vision and aesthetic. His piece, Maximum Sensation is comprised of fourteen skateboards that are each topped with a fragment of a Muslim prayer rug. Some of the rugs are for women and depict floral motifs, and some are adorned with architectural patterns for men. The boards are hung to appear as if they are in a kick-flip motion – a maneuver, or trick, used by skaters to subvert the board 360 degrees while in motion. The relationship between the prayer rug and skateboard is unusual, but commonalities can be highlighted: both cultures are inclusive and include generations of passionate followers. Some would argue that skateboarding is also a spiritual experience. By merging East and West ideas and customs, the now richly patterned skateboard takes on a new meaning, as does the prayer rug. |

|

Ana Gómez

Maruchan from the Disposable series, 2009 Stoneware ceramic, glaze, gold varnish In our contemporary world, preparing a daily meal with time and love, and serving it to family, friends, and community members feels like a quaint activity from another time. After a busy day, we are more likely to grab something to-go or pour hot water over dehydrated noodles – like the Maruchan noodle soup cup - than we are to eat a home-cooked meal. With her Disposables series, Mexican artist Ana Gómez uses ceramics—an ancient material that has been part of every home and kitchen for centuries— to make a statement about today’s quick-fix, take-out culture. To create her ceramics, Gómez collaborates with Mexican artisans who use traditional pigments, designs, and glaze techniques. For her piece, Maruchan, Gómez crafted 30 containers emblazoned with the Maruchan logo – a brand recognized worldwide as a symbol of processed convenience on the go. The container’s mobility plays into another significant trend that Gómez has observed: it’s not just what we eat, but where we eat it. She has noted that the family roles and social dynamics that were once woven through our lives and communities are now “diluted” and replaced by lives that are always in motion. |

|

Ana Gómez

Vitrina from the Disposable series, 2010 Porcelain ceramic with enamel, gold varnish, decals and hand-painted, shelves, vinyl Mexican artist Ana Gómez designs and creates a range of ceramic take-out containers to make a statement about our disposable culture. Gómez’s work has been described as a “modern portrait” of our lives, effectively illustrating how take-out containers have replaced dinnerware. With its strong socio-political message, her Disposable series reminds the viewer of the tradition of feasting with family, cultural associations tied to food, and the art of presentation. Digging deeper, viewers may find themselves thinking about what has replaced the family dinner (perhaps it is the busyness of life: long commute hours and frantic schedules) and what now passes as nourishment for the body and soul. Several of the disposable containers in Gómez’s installation, Vitrina, were painted to mimic 16th century Talavera pottery designs of Puebla, Mexico, and were developed in collaboration with Mexican artisans who used traditional pigment & glaze techniques. This type of ceramic is called Majolica, and it is distinguished by its milky-white ground glaze and cobalt blue traditional patterning—usually a flower-pattern with detailed filigree. The design reflects a mix of historic patterning from indigenous, European, Arab, and Chinese influences. For many years, Talavera pottery has been embraced by the country as distinctly “Mexican” (and particularly representative of the Puebla region), and is a popular tourist souvenir and exported good. |

|

Shirin Hosseinvand

Camouflage, 2019 Persian mirror mosiac Shirin Hosseinvand Star cluster at night, 2019 Persian mirror mosiac Shirin Hosseinvand A beam of sunshine, 2019 Persian mirror mosiac Shirin Hosseinvand Emerald, 2019 Persian mirror mosiac Shirin Hosseinvand is an Iranian American artist who is known for merging ancient Iranian mosaic mirror work with popular consumer objects like the ubiquitous Coca-Cola can. As Hosseinvand states, she combines these ideas to “give an ethnic identity to the concept of globalization and mass production.” Coke, one of the most mass-produced products in the world, is easily identifiable across the globe by its trademark red can and white script lettering. In Hosseinvand’s mirrored versions, she makes the can much more culturally palatable by using colors and languages associated with particular countries, creating a much more personal “product.” From the outset of her process, Hosseinvand designs geometric patterns around a Coke can sculpture and then works with skilled Iranian glasscutters to cut colored mirror, piece by piece, into a multitude of different shapes. Each can is exquisitely unique and tells its own story. |

|

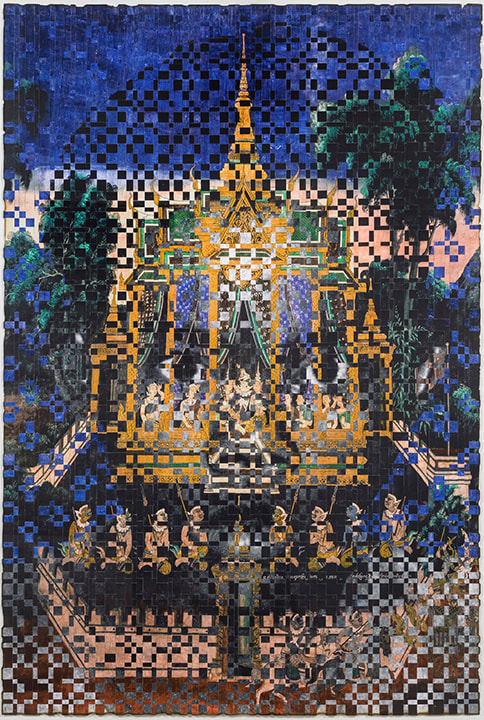

Dinh Q Lê

Cracked Reamker, 2017 C-print, linen tape Courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Santa Monica, CA After fleeing Vietnam as a child in the 1970s, Dinh Q. Lê landed in Los Angeles with his family. Lê eventually studied photography at U.C. Santa Barbara and went on to create work inspired by his culture and the impact Hollywood movies have had on his community. Lê had avoided the Vietnam War movies of the 1980s and 1990s until one day he decided to watch them. Hollywood’s dramatic depictions of the war and his people were unsettling to Lê. He began to think about how we “weave” or construct narratives to create an alternative reality in our minds. He began to weave Hollywood imagery, images of historic temples in the reamker style (a Cambodian poem based on the Sanskrit Ramayana epic), and photographs of prisoners from the infamous Cambodian S-21 prison camp to create complex and textured artworks that speak to knowledge and memory. His work asks pointed questions: what do we really know about war? Could reality and memory create a hybrid history? Using traditional Vietnamese weaving methods used to create grass mats, Lê’s woven, abstracted photographs challenge the viewer to question their beliefs and memory. |

|

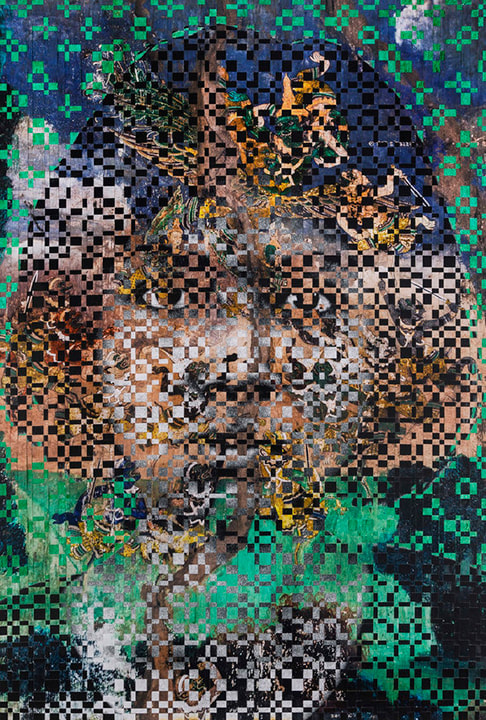

Dinh Q. Lê

Portrait of the Palace, 2017 C-print, linen tape Courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Santa Monica, CA Photographer, Dinh Q. Lê was born in 1968 in Hà Tiên, Vietnam. When he was 10 years old, his family fled for America during the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia. Lê’s photographic work has evolved to represent and reflect his memories from this time in Southeast Asia. Featured in this exhibition are two portraits of Cambodian child prisoners from the Cambodian Civil War. His piece, Portrait of the Palace, features one such prisoner from the infamous S-21 prison, where thousands of people were tortured and killed between 1975 and 1979. To create these woven portraits, Lê utilizes a traditional weaving method that his aunt taught him—this same technique has been used to create Vietnamese grass mats for generations. Lê starts by creating a Chromogenic print—also known as a C-print—made from a color negative or slide. He enlarges the original image and then slices the images into thin strips. Weaving the figure together with images of traditional Cambodian structures and motifs, distorts the portrait, creating a complex hybrid that tells a story of past and present. Each artwork is finished with linen tape to hold the photo slices together, creating a unique photographic tapestry. |

|

Steven Young Lee

Gourd Vases with Lotus Pattern, 2015 Porcelain ceramic, white slip, glaze Courtesy of Duane Reed Gallery, St. Louis, MO Steven Young Lee (b. 1975) grew up in the United States, the son of Korean immigrants. As such, he has often found himself situated between two cultures and often “looking from one side to the other,” as he states. As an adult, Lee has lived all over the world – from major metropolises, like New York and Shanghai, to rural communities, like Jingdezhen, China, and Helena, Montana. These varied experiences have influenced Lee to address ideas of identity, assimilation, place, and belonging through his work. Having begun his artistic career learning Asian pottery techniques in a Western school, Lee also investigates the source and ownership of cultural influence. His deconstructed and imperfect ceramic forms lead us to question failure, expectation, and intent as we consider and redefine concepts of beauty. |

Jaydan Moore

Specimen #5, 2013

Silver-plated platters

Courtesy of Ornamentum, Hudson, NY

Jaydan Moore

Specimen (two rectangles), 2013

Silver-plated platters

Courtesy of Ornamentum, Hudson, NY

Jaydan Moore grew up in a family of fourth-generation tombstone makers. He spent most of his childhood sitting in his family’s office, listening to people translate the lives of their loved ones into imagery, dates, and quotes that would represent them forever at their gravesite. Moore’s family also owned a rental storage business filled with containers of stuff that people wanted to keep but not live with. The dialogue between these two experiences inspired him to consider, through his work, how people define themselves and others. Moore’s reclaimed and surreal hybrid pieces of discarded heirlooms reflect the relevance of these objects in our contemporary world. Are these re-envisioned heirlooms now more valuable to society or less? His work poses questions of commodification, ownership, permanency, and the ecological impact imposed by our desire to collect.

Specimen #5, 2013

Silver-plated platters

Courtesy of Ornamentum, Hudson, NY

Jaydan Moore

Specimen (two rectangles), 2013

Silver-plated platters

Courtesy of Ornamentum, Hudson, NY

Jaydan Moore grew up in a family of fourth-generation tombstone makers. He spent most of his childhood sitting in his family’s office, listening to people translate the lives of their loved ones into imagery, dates, and quotes that would represent them forever at their gravesite. Moore’s family also owned a rental storage business filled with containers of stuff that people wanted to keep but not live with. The dialogue between these two experiences inspired him to consider, through his work, how people define themselves and others. Moore’s reclaimed and surreal hybrid pieces of discarded heirlooms reflect the relevance of these objects in our contemporary world. Are these re-envisioned heirlooms now more valuable to society or less? His work poses questions of commodification, ownership, permanency, and the ecological impact imposed by our desire to collect.

Ramekon O'Arwisters

Mending #16, 2017

Fabric, ceramic shards

Courtesy of Patricia Sweetow Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Ramekon O'Arwisters

Mending #22, 2017

Fabric, ceramic shards

Courtesy of Patricia Sweetow Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Ramekon O’Arwisters grew up in North Carolina during the 1960s. As a child, he spent a great deal of time with his paternal grandmother making quilts. O’Arwisters, who is gay, admits that the time consuming himself with quilt work tucked away with his grandmother, was an attempt to conceal his identity. “I was a little black boy hiding my queer self from my family,” he says in an artist statement. O’Arwisters says that the broken ceramics in his Mending series represent the human body, which like a jug, is also a vessel. When the human vessel is broken it needs to be mended, not neglected. O’Arwisters’ mended broken ceramic sculptures not only represents healing and the urge to help one another but are seemingly a gentle nod to his grandmother who provided care and comfort during his formative childhood years.

Mending #16, 2017

Fabric, ceramic shards

Courtesy of Patricia Sweetow Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Ramekon O'Arwisters

Mending #22, 2017

Fabric, ceramic shards

Courtesy of Patricia Sweetow Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Ramekon O’Arwisters grew up in North Carolina during the 1960s. As a child, he spent a great deal of time with his paternal grandmother making quilts. O’Arwisters, who is gay, admits that the time consuming himself with quilt work tucked away with his grandmother, was an attempt to conceal his identity. “I was a little black boy hiding my queer self from my family,” he says in an artist statement. O’Arwisters says that the broken ceramics in his Mending series represent the human body, which like a jug, is also a vessel. When the human vessel is broken it needs to be mended, not neglected. O’Arwisters’ mended broken ceramic sculptures not only represents healing and the urge to help one another but are seemingly a gentle nod to his grandmother who provided care and comfort during his formative childhood years.

|

Jason Seife

Ocean Bed, 2016-2017 oil and acrylic on canvas Courtesy of the Rodef Family Collection, San Diego, CA Jason Seife is a Miami-based artist whose work is inspired by Middle Eastern artistry, particularly carpet design. He was introduced to rug weaving as an artistic expression by his Persian grandmother and grew up watching her make carpets. Rather than replicate the art form as it has existed for thousands of years, Seife creates oil and acrylic paintings of Persian carpets that also includes textile patterns from other Middle Eastern countries to build his own artistic “language.” While painting is Seife’s passion, he is not limited to canvases. He has designed a wide range of items from album artwork to jewelry and merchandise that often reference his Middle Eastern heritage. Seife takes “great pride in both continuing this (traditional) art form as well as finding new ways to push it and continue to make it exciting and appealing for future generations.” Seife’s use of modern materials and compositions ultimately subverts the viewer’s expectations to create a new experience. |

|

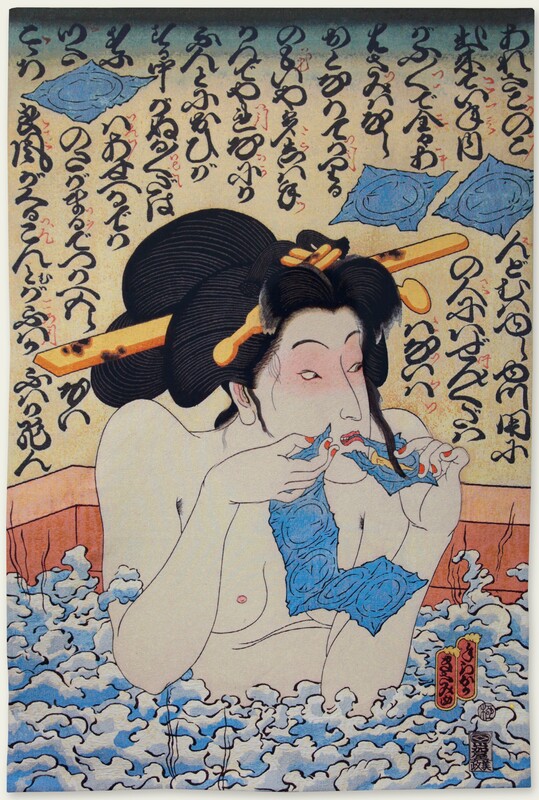

Masami Teraoka

Geisha in Ofuro, 2011 Jacquard tapestry Courtesy of Magnolia Editions, Oakland, CA Masami Teraoka, a Japanese-born, Hawaii-based artist merges visual narratives and traditional Japanese Ukiyo-e iconography in his work to consider contemporary issues, including cultural collision, religious and political hypocrisy, and sexual taboos. Teraoka’s tapestry, Geisha in Ofuro, began as a watercolor painting on canvas from the artist’s 1988 AIDS series – a series he began shortly after learning that a friend’s child was stricken with the disease. In 2008, Teraoka reworked the image as a woodblock print. As a tapestry, his Geisha takes on an especially monumental form. Teraoka’s reflection on the effect of AIDS within Japan’s sex industry (the mizu-shobai or “water business”) suggests that even in a world of fantasy, awareness is paramount, and a simple act of self-protection can be a measure of strength. Teraoka’s Geisha has been described as a safe-sex heroine, but if you look closer she apparently has had a close call…her kanzashi (hair ornaments) appear to be singed by fire, suggestive of Kaposi’s sarcoma – a detrimental side effect of AIDS. |

This Exhibition is made possible with the support of the Michigan Council for Arts & Cultural Affairs.