It’s possible to fall in love with the line on a page. A line drawn by someone else - an Old Master or New, but all the sweeter if it’s yours and one you’ve strived over many years to achieve.

Life drawing is like that for me - There is nothing better than having that dusty charcoal in your hand, empty, slightly intimidating blank page in front of you, a real live person posing for you, your cohorts nearby - the timer sounds and you begin - the earnest quiet of shared endeavor, sounds of crayon on rough newsprint - get the gesture, don’t render details until you get the structure right, hips, shoulder girdle; each person in his own world of concentrated effort and discovery. No place I’d rather be. In almost all the towns I’ve lived over the past 50 years, I’ve joined a life drawing class. From the more traditional art schools: Art Students League and National Academy School in New York to the smallest group of 5 or 6 in someone’s home around a posed person, our easels and drawing pads poised for action. It’s always the same excitement: that collective effort- each with his own style, experience, seeing as each is seeing - trying to get it right, or at least something that pleases.

Of course, figure drawing has been going on for centuries - the starting point of an art education. Having a living, breathing person in front of you instead of a vase, some peaches and a draped cloth changes the dynamic completely. The air is charged with something engaging and unpredictable - you are in a connection with the subject that demands a new attentiveness and the illusive struggle begins.

Learning anatomy, composition, volume, proportion, gesture, line, training the eye to see what is really there takes time and dedication. It’s a coordination and a bringing it all together much as any musician or athlete draws upon his or her years of practice to achieve success. And it does take practice. For those of us in the game, years of practice makes that worth it because every now and then something magical happens.

Look at any of the major artists of the recent past - abstract or otherwise - Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, Paul Klee, Willem de Kooning, and, indeed, Marshall Fredericks. They all started with the basics - and life drawing. And knowing that unless you understand and thoroughly render it realistically, it is hard to create something stylized or abstract with any real authority. A valuable tool in the toolbox. And, of course, there you are, following in the footsteps of the great Masters - with that pad of paper and charcoal or crayon - just as they did on their road to mastery.

So you wait for those sublime moments when you’ve caught something that moves you - insertions of neck to torso, strong translation of leg to hip, a coordination of lines that makes it come alive and creates an emotional reaction - and, like a golfer who hits a perfect shot - you’re off and running - after the vanishing horizon of the perfect line.

Essay by Michaele Duffy Kramer

Life drawing is like that for me - There is nothing better than having that dusty charcoal in your hand, empty, slightly intimidating blank page in front of you, a real live person posing for you, your cohorts nearby - the timer sounds and you begin - the earnest quiet of shared endeavor, sounds of crayon on rough newsprint - get the gesture, don’t render details until you get the structure right, hips, shoulder girdle; each person in his own world of concentrated effort and discovery. No place I’d rather be. In almost all the towns I’ve lived over the past 50 years, I’ve joined a life drawing class. From the more traditional art schools: Art Students League and National Academy School in New York to the smallest group of 5 or 6 in someone’s home around a posed person, our easels and drawing pads poised for action. It’s always the same excitement: that collective effort- each with his own style, experience, seeing as each is seeing - trying to get it right, or at least something that pleases.

Of course, figure drawing has been going on for centuries - the starting point of an art education. Having a living, breathing person in front of you instead of a vase, some peaches and a draped cloth changes the dynamic completely. The air is charged with something engaging and unpredictable - you are in a connection with the subject that demands a new attentiveness and the illusive struggle begins.

Learning anatomy, composition, volume, proportion, gesture, line, training the eye to see what is really there takes time and dedication. It’s a coordination and a bringing it all together much as any musician or athlete draws upon his or her years of practice to achieve success. And it does take practice. For those of us in the game, years of practice makes that worth it because every now and then something magical happens.

Look at any of the major artists of the recent past - abstract or otherwise - Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, Paul Klee, Willem de Kooning, and, indeed, Marshall Fredericks. They all started with the basics - and life drawing. And knowing that unless you understand and thoroughly render it realistically, it is hard to create something stylized or abstract with any real authority. A valuable tool in the toolbox. And, of course, there you are, following in the footsteps of the great Masters - with that pad of paper and charcoal or crayon - just as they did on their road to mastery.

So you wait for those sublime moments when you’ve caught something that moves you - insertions of neck to torso, strong translation of leg to hip, a coordination of lines that makes it come alive and creates an emotional reaction - and, like a golfer who hits a perfect shot - you’re off and running - after the vanishing horizon of the perfect line.

Essay by Michaele Duffy Kramer

TRY YOUR HAND AT DRAWING WITH These ACTIVITies

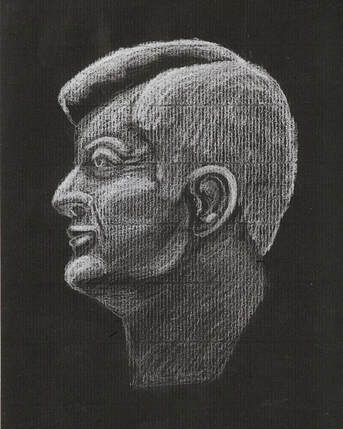

Sculptural Figure Drawing

Choose one of the sculptural figures below to draw. The high definition videos below can be paused at any location to allow you to sketch. Enlarge videos to full screen for best viewing. Share your drawings with us on Facebook.

Choose one of the sculptural figures below to draw. The high definition videos below can be paused at any location to allow you to sketch. Enlarge videos to full screen for best viewing. Share your drawings with us on Facebook.

|

|

|

|

|

|

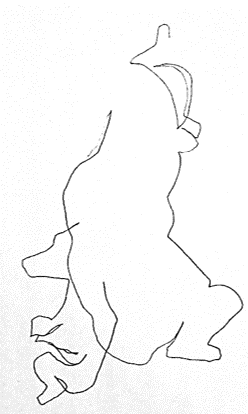

Blind Contour and Reverse Value Drawing

Click on the images above to try your hand at blind contour and reverse value drawing. Use the virtual museum to choose a sculpture to draw.

Click on the images above to try your hand at blind contour and reverse value drawing. Use the virtual museum to choose a sculpture to draw.

“On Figure Drawing” by Valerie Mann

We have such fraught relationships with our bodies. We work on them for better health, to keep in shape and to reduce stress. We are happy when they work properly or help us achieve a goal or unhappy with them when they fail us or don’t meet some higher standard. We are familiar with each little mark, curve and scar and have the daily opportunity to stare at our unclad bodies in mirrors. We don’t, however, have the opportunity to really study a nude human form that is not our own on a daily basis. Drawing from life gives us the opportunity to study the human body from an emotionally detached position and a point of view that is all about inquiry.

I have found that studying the human form gives me a greater appreciation for diverse body types. A sense of deep inquiry takes over at the beginning of each drawing as I record the gesture of the pose and the accurate details that separate one model from the next. As an instructor, I can address the figure from a formal standpoint and get students to imagine what the model is feeling, the gesture of the form, where the weight is supported, and how some parts of the body relate to other parts of the body. Representing the figure on a flat paper surface and trying to make it look three-dimensional can pose a real challenge! After drawing the figure, I find myself thinking how my own body occupies and moves through space.

And then there is time and age and what that does to the body. It affects each of us differently. I often wonder, when we have an older (70+) model in the classroom, if my students fully appreciate this unique opportunity. It’s like a glimpse into the future. Again, we can approach studying the figure from a point of inquiry and curiosity, which lets us appreciate and marvel at the complexity of the human form.

Looking at Marshall Fredericks’s drawings, I see that he was trying to understand certain parts of each figure - whether it was the placement of the feet in space, the foreshortening of an arm or the way the light created shadows on the body. Drawing was certainly practice for his sculpture, but also giving him an immediate result, as compared to his sculptural work. I see that he was enjoying the practice of deep inquiry within these drawings.

Valerie Mann, artist

We have such fraught relationships with our bodies. We work on them for better health, to keep in shape and to reduce stress. We are happy when they work properly or help us achieve a goal or unhappy with them when they fail us or don’t meet some higher standard. We are familiar with each little mark, curve and scar and have the daily opportunity to stare at our unclad bodies in mirrors. We don’t, however, have the opportunity to really study a nude human form that is not our own on a daily basis. Drawing from life gives us the opportunity to study the human body from an emotionally detached position and a point of view that is all about inquiry.

I have found that studying the human form gives me a greater appreciation for diverse body types. A sense of deep inquiry takes over at the beginning of each drawing as I record the gesture of the pose and the accurate details that separate one model from the next. As an instructor, I can address the figure from a formal standpoint and get students to imagine what the model is feeling, the gesture of the form, where the weight is supported, and how some parts of the body relate to other parts of the body. Representing the figure on a flat paper surface and trying to make it look three-dimensional can pose a real challenge! After drawing the figure, I find myself thinking how my own body occupies and moves through space.

And then there is time and age and what that does to the body. It affects each of us differently. I often wonder, when we have an older (70+) model in the classroom, if my students fully appreciate this unique opportunity. It’s like a glimpse into the future. Again, we can approach studying the figure from a point of inquiry and curiosity, which lets us appreciate and marvel at the complexity of the human form.

Looking at Marshall Fredericks’s drawings, I see that he was trying to understand certain parts of each figure - whether it was the placement of the feet in space, the foreshortening of an arm or the way the light created shadows on the body. Drawing was certainly practice for his sculpture, but also giving him an immediate result, as compared to his sculptural work. I see that he was enjoying the practice of deep inquiry within these drawings.

Valerie Mann, artist