The Exhibition

Imagined West

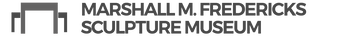

“The West is no longer the west of picturesque and stirring events. Romance and adventure have been beaten down in the rush of civilization.” —Frederic Remington, 1907

As in the quote above, these sculptures tell fictional stories of an American West that was an untouched, romantic, or “uncivilized” frontier—ripe for adventuring. That wasn’t true.

Made in the 1900s, their vivid details transported viewers back in time from bustling cities to the mountains and plains of an imagined “Wild West.” Images of rugged cowboys taming nature and defeated Native Americans reflect the racist attitudes of their makers and promoted the false belief that Indigenous extinction was an inevitability.

What invented stories do monumental sculptures continue to tell today?

“The West is no longer the west of picturesque and stirring events. Romance and adventure have been beaten down in the rush of civilization.” —Frederic Remington, 1907

As in the quote above, these sculptures tell fictional stories of an American West that was an untouched, romantic, or “uncivilized” frontier—ripe for adventuring. That wasn’t true.

Made in the 1900s, their vivid details transported viewers back in time from bustling cities to the mountains and plains of an imagined “Wild West.” Images of rugged cowboys taming nature and defeated Native Americans reflect the racist attitudes of their makers and promoted the false belief that Indigenous extinction was an inevitability.

What invented stories do monumental sculptures continue to tell today?

Classical Visions

“No work in sculpture, however well wrought out physically, results in excellence, unless it rests upon, and is sustained by the dignity of a moral or intellectual intention.” —Erastus Dow Palmer, 1856

What did the sculptors in this section intend? By evoking styles from ancient Greece and Rome, they hoped to connect those cultures’ legacies—of democracy, patriotic devotion, and military prowess—to America’s future.

In the mid-1800s, the United States was young—about 70 years old. Industrialization, territorial expansion, and the Civil War were shaping the nation. Against a backdrop of tumultuous change, these works conveyed timelessness, permanence, and stability.

What Greek and Roman influence do you still see today in public sculpture, government buildings, and pop culture? Think about columns, marble, togas, and mythological figures like Hercules.

“No work in sculpture, however well wrought out physically, results in excellence, unless it rests upon, and is sustained by the dignity of a moral or intellectual intention.” —Erastus Dow Palmer, 1856

What did the sculptors in this section intend? By evoking styles from ancient Greece and Rome, they hoped to connect those cultures’ legacies—of democracy, patriotic devotion, and military prowess—to America’s future.

In the mid-1800s, the United States was young—about 70 years old. Industrialization, territorial expansion, and the Civil War were shaping the nation. Against a backdrop of tumultuous change, these works conveyed timelessness, permanence, and stability.

What Greek and Roman influence do you still see today in public sculpture, government buildings, and pop culture? Think about columns, marble, togas, and mythological figures like Hercules.

Modern Form

“What I wanted was to look for beauty in the everyday world, to catch the joy and swing of modern American life.” —Bessie Potter Vonnoh, 1925

In the early 1900s, American sculptors working in a variety of styles wanted to break with past conventions and create art that reflected modern life.

The sculptures in this section reflect changes in:

Which individual from your everyday life would you choose to celebrate in sculpture?

“What I wanted was to look for beauty in the everyday world, to catch the joy and swing of modern American life.” —Bessie Potter Vonnoh, 1925

In the early 1900s, American sculptors working in a variety of styles wanted to break with past conventions and create art that reflected modern life.

The sculptures in this section reflect changes in:

- Voice — women sculptors become more prominent.

- Style — simplified forms and smoother surfaces move the needle toward abstraction.

- Subject — everyday people receive heroic treatment in bronze.

Which individual from your everyday life would you choose to celebrate in sculpture?

New Monuments

“In the 19th century you could go to a school where they’d teach horse anatomy and . . . you’d know how to make a monument by the time you got out. Art school in my day was more about exploring ideas or developing a personality in your work.” —Richard Hunt, 2015

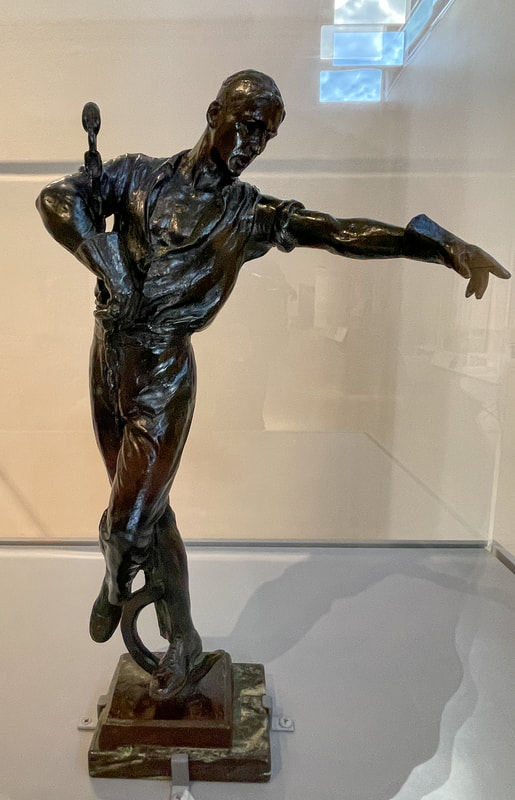

In the late 1900s, artists reconsidered the relevance of traditional sculpture with its elevated human subjects and expensive materials like marble and bronze.

Some rejected figurative subjects altogether for abstract forms that expressed an idea or emotion. Some elevated everyday objects to the status of art. Others responded with the innovative use of new or atypical materials such as plastic, steel, and found objects.

Altogether, they sought to create a conversation around the social role and function of monumental sculpture and to conceive new possibilities for what monuments could be.

Which sculpture in this section most challenges your ideas about what a monument is?

“In the 19th century you could go to a school where they’d teach horse anatomy and . . . you’d know how to make a monument by the time you got out. Art school in my day was more about exploring ideas or developing a personality in your work.” —Richard Hunt, 2015

In the late 1900s, artists reconsidered the relevance of traditional sculpture with its elevated human subjects and expensive materials like marble and bronze.

Some rejected figurative subjects altogether for abstract forms that expressed an idea or emotion. Some elevated everyday objects to the status of art. Others responded with the innovative use of new or atypical materials such as plastic, steel, and found objects.

Altogether, they sought to create a conversation around the social role and function of monumental sculpture and to conceive new possibilities for what monuments could be.

Which sculpture in this section most challenges your ideas about what a monument is?

Claes Oldenburg "Alphabet / Good Humor"

Slide to compare the drawing to the final sculpture.

Slide to compare the drawing to the final sculpture.

How Should We Remember?

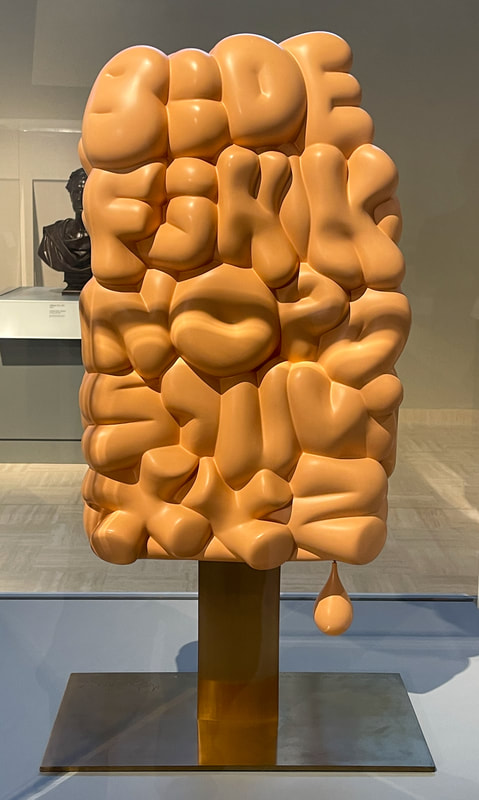

“For me, the whole thing about modern art is, you can invent your own game and all the rules.” —Melvin Edwards, 2014

An intimate box of art objects can be both a memorial and activism. A monument dedicated to a sports icon can transform into a call for equal rights.

The works in this section stretch the capacity of monuments to commemorate people, events, and ideas. No longer just figurative representations funded and controlled by the person who commissioned them, these objects represent complicated life legacies, entire communities, and even create space for memories to be made.

Can you think of a time a monument took on a new meaning once it became public?

“For me, the whole thing about modern art is, you can invent your own game and all the rules.” —Melvin Edwards, 2014

An intimate box of art objects can be both a memorial and activism. A monument dedicated to a sports icon can transform into a call for equal rights.

The works in this section stretch the capacity of monuments to commemorate people, events, and ideas. No longer just figurative representations funded and controlled by the person who commissioned them, these objects represent complicated life legacies, entire communities, and even create space for memories to be made.

Can you think of a time a monument took on a new meaning once it became public?