Although Marshall M. Fredericks (1908–1998), was known mainly for his figurative public sculptures, the public has rarely seen his two-dimensional studies of life drawings and finished artworks. Marshall Fredericks’s life drawings provide a vital link to interpreting public sculpture in the 20th century and add to the history of American sculpture.

He graduated from the Cleveland School of Art in 1930 and then journeyed to Sweden on a fellowship to study with sculptor Carl Milles (1875-1955). Then in 1932 Carl Milles invited Fredericks to join the staff of Cranbrook Academy of Art, Cranbrook and Kingswood Schools in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan where he taught until he enlisted in the armed forces in 1942. After serving in WWII, he obtained studios and produced public art commissions. In his 70-year career, Fredericks created more than 500 sculpture commissions in diverse settings and cities in the US and abroad. The highlight of his career was the establishment of the Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum in 1988 on the campus of Saginaw Valley State University.

The Museum archives are unique as few museums house a complete representation of both an artist’s work and their personal effects, allowing for studies of artistic processes, creative development and art history. The Museum archives contain approximately 10 linear feet of Fredericks’s life figure drawings, sculpture project sketches, presentation drawings and working drawings.

If we examine figure drawing in the context of human history, prehistoric imagery was mostly animal forms and rarely human forms. But with the growth of modern humans’ globally, the human figure becomes more prominent in visual representations, both in realistic and abstract forms. Three well-known Renaissance artists: Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1519), Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) and Raphael (Raffaello Santi) (1483-1520) produced many figure drawings. Their figurative drawing studies and human anatomy became a standard for visual art education and training.

The practice of life figure drawing greatly enhanced the anatomical accuracy of the figurative arts artists produced. It’s an exercise they practice frequently and most often will get together with other artists, hire a model and practice their skill to keep current. Sometime in the early 1950s, Fredericks may have done just that, honing his skills with other artists. He also was known to hire his own models for sculpture commissions.

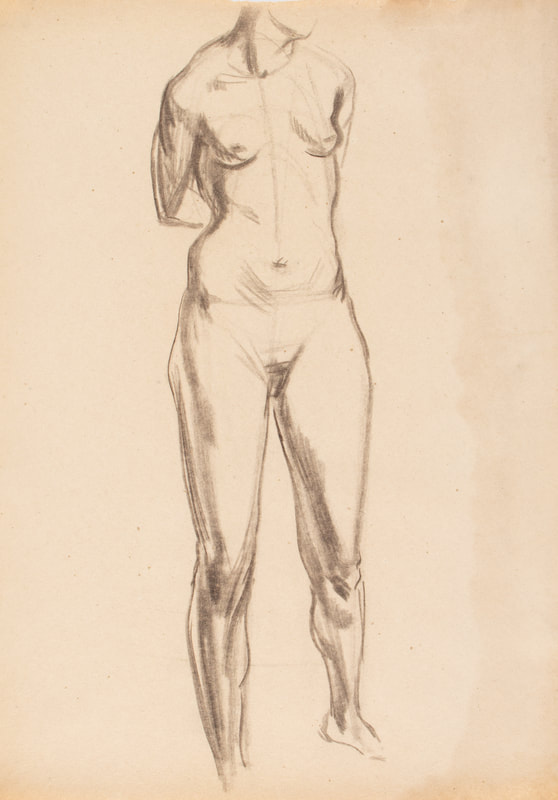

The series of drawings in this exhibition display both male and female subjects. His drawings aren’t meant to be finished polished works but mere studies and practice in the art of the “live” human form. Additionally, he often used a small male plaster anatomical model, found in Sculptor’s Studio, for muscle accuracy; its surface darkened from the many times he referenced it with his clay-covered hands and fingers.

His drawings display remarkable draftsmanship of the human form. They illustrate his artistic process and creative development for translation into three-dimensional works as seen in the Main Gallery of the Museum and his many figurative public sculptures. From an art history perspective, they are a great contribution to the study of American sculpture, drawing and of course cultural heritage.

He graduated from the Cleveland School of Art in 1930 and then journeyed to Sweden on a fellowship to study with sculptor Carl Milles (1875-1955). Then in 1932 Carl Milles invited Fredericks to join the staff of Cranbrook Academy of Art, Cranbrook and Kingswood Schools in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan where he taught until he enlisted in the armed forces in 1942. After serving in WWII, he obtained studios and produced public art commissions. In his 70-year career, Fredericks created more than 500 sculpture commissions in diverse settings and cities in the US and abroad. The highlight of his career was the establishment of the Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum in 1988 on the campus of Saginaw Valley State University.

The Museum archives are unique as few museums house a complete representation of both an artist’s work and their personal effects, allowing for studies of artistic processes, creative development and art history. The Museum archives contain approximately 10 linear feet of Fredericks’s life figure drawings, sculpture project sketches, presentation drawings and working drawings.

If we examine figure drawing in the context of human history, prehistoric imagery was mostly animal forms and rarely human forms. But with the growth of modern humans’ globally, the human figure becomes more prominent in visual representations, both in realistic and abstract forms. Three well-known Renaissance artists: Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1519), Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) and Raphael (Raffaello Santi) (1483-1520) produced many figure drawings. Their figurative drawing studies and human anatomy became a standard for visual art education and training.

The practice of life figure drawing greatly enhanced the anatomical accuracy of the figurative arts artists produced. It’s an exercise they practice frequently and most often will get together with other artists, hire a model and practice their skill to keep current. Sometime in the early 1950s, Fredericks may have done just that, honing his skills with other artists. He also was known to hire his own models for sculpture commissions.

The series of drawings in this exhibition display both male and female subjects. His drawings aren’t meant to be finished polished works but mere studies and practice in the art of the “live” human form. Additionally, he often used a small male plaster anatomical model, found in Sculptor’s Studio, for muscle accuracy; its surface darkened from the many times he referenced it with his clay-covered hands and fingers.

His drawings display remarkable draftsmanship of the human form. They illustrate his artistic process and creative development for translation into three-dimensional works as seen in the Main Gallery of the Museum and his many figurative public sculptures. From an art history perspective, they are a great contribution to the study of American sculpture, drawing and of course cultural heritage.

LEARN ABOUT FREDERICKS - FROM 2D TO 3D

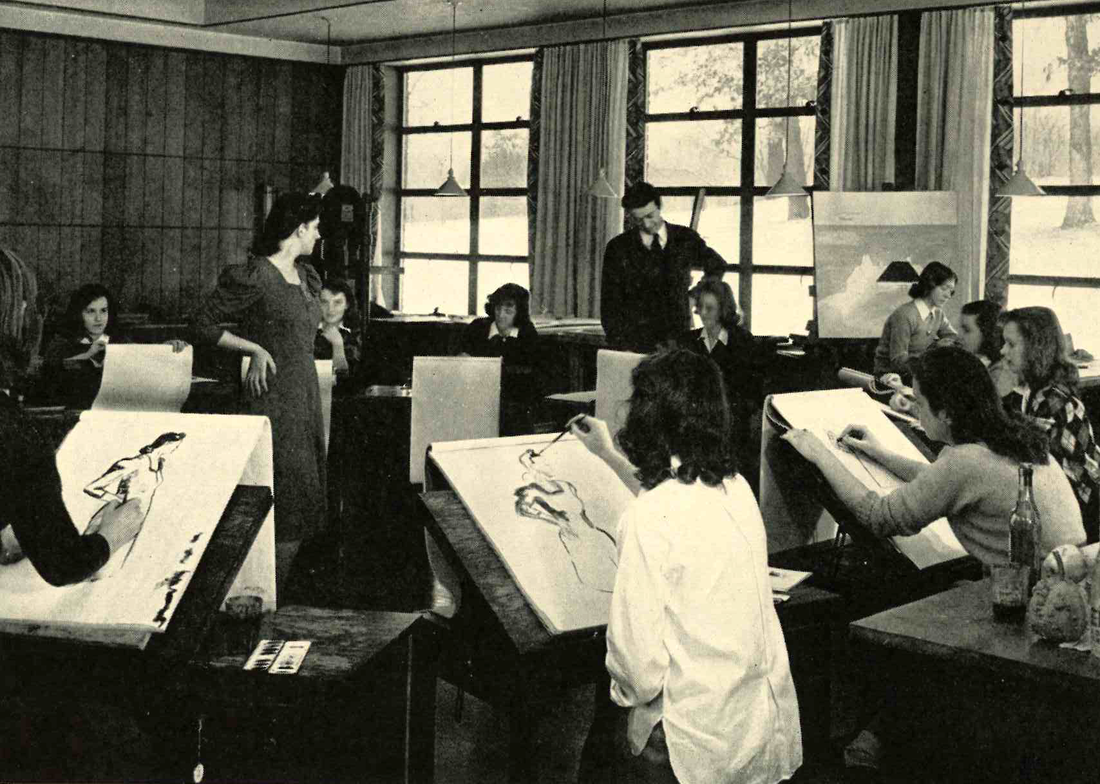

Marshall Fredericks taught drawing classes at Kingswood School for Girls, located in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, during the 1930s.

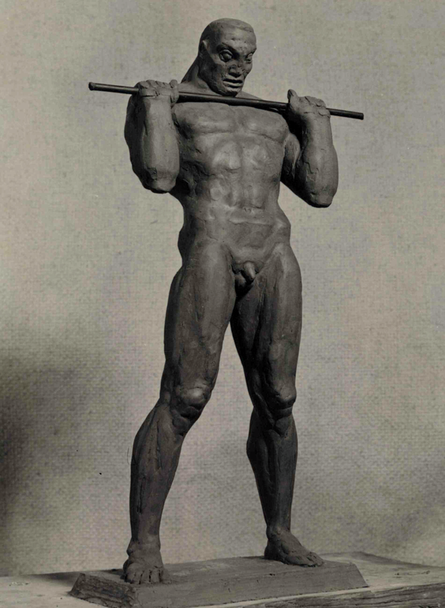

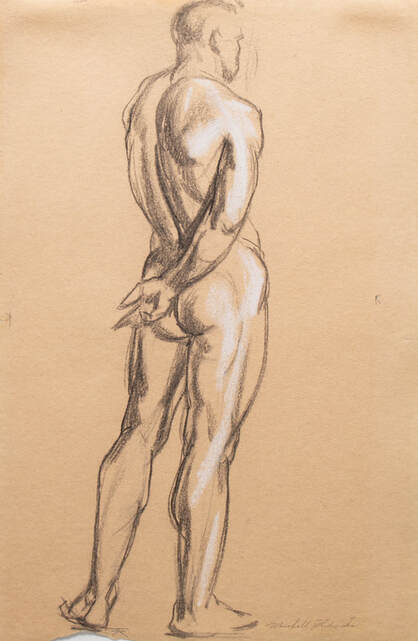

Many of Marshall Fredericks’s figure studies were used in preparation for his sculptures. The above sculpture from 1950 is titled "The Strong Man" and the drawing on the right is a figure study of a model that may have been the model for that sculpture. Notice the muscle structure is quite similar.

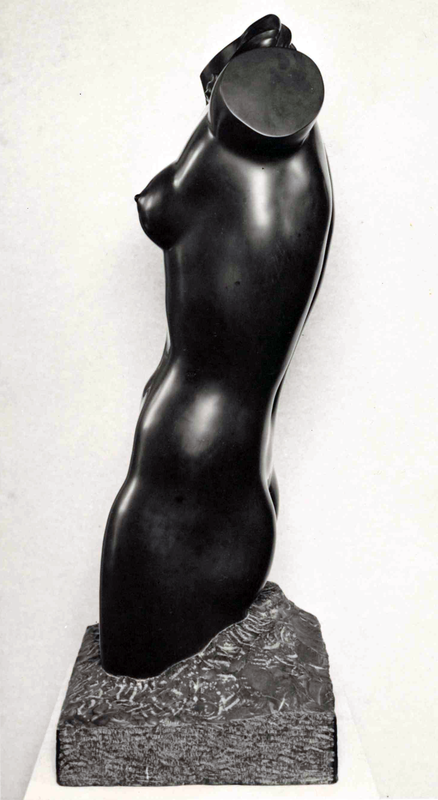

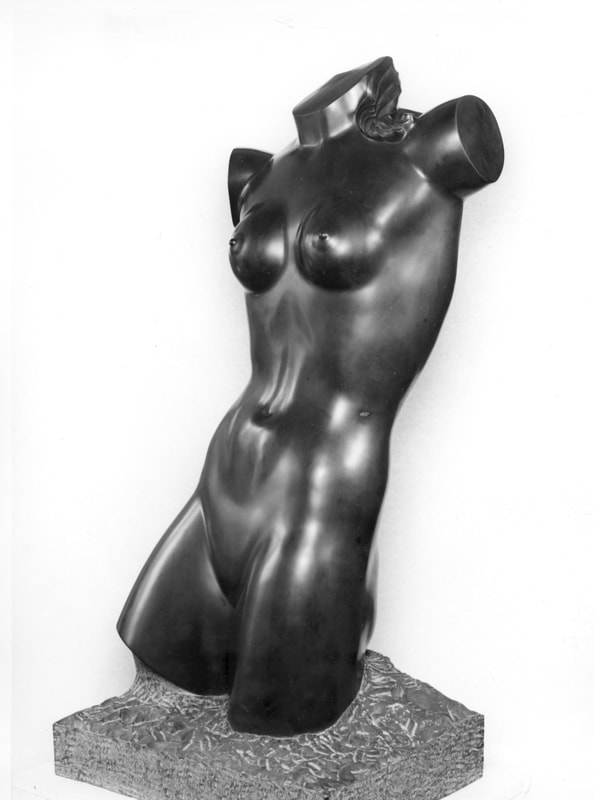

The above sculpture from 1938 is titled "Torso of a Dancer". The images below allow you to see how the artist utilized his 2D drawings and transformed them to beautiful 3D sculptures.

Marshall Fredericks At his desk

Below is a slideshow selection of drawing-related objects housed in the Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum archives. These objects were originally from Marshall Fredericks’s sculpture studio and used by the artist during his long, prolific career. These are just a few examples of the dozens of drawing objects located in the museum archives.

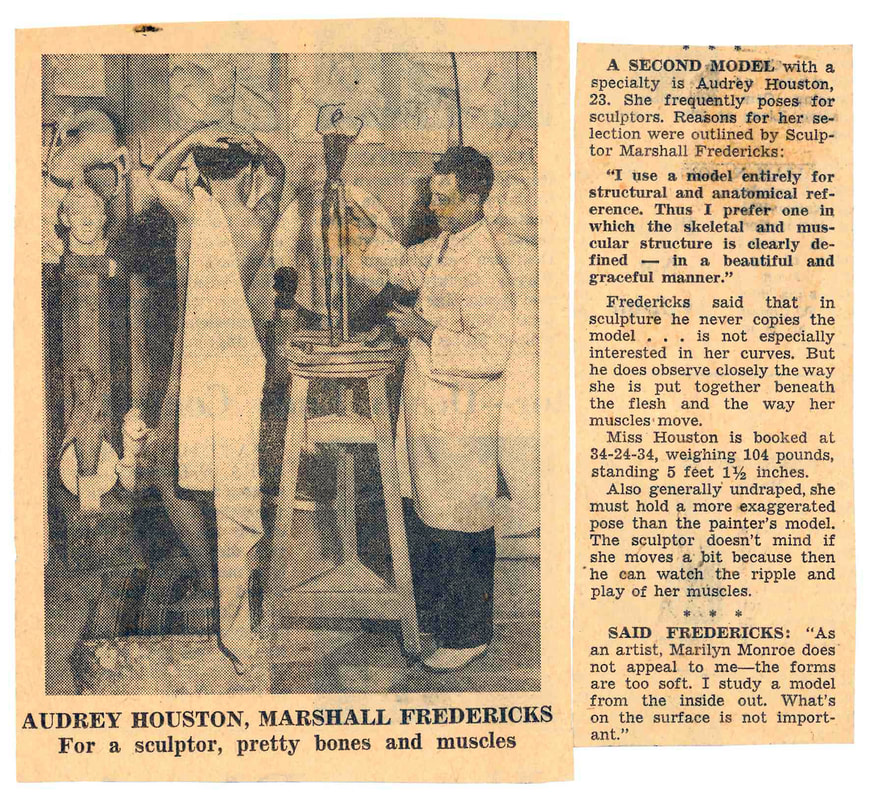

AUDREY HOUSTON "PRETTY BONES AND MUSCLES"

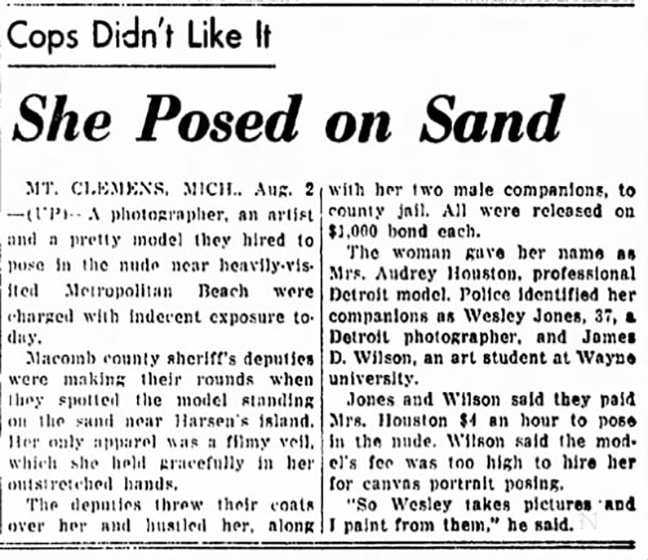

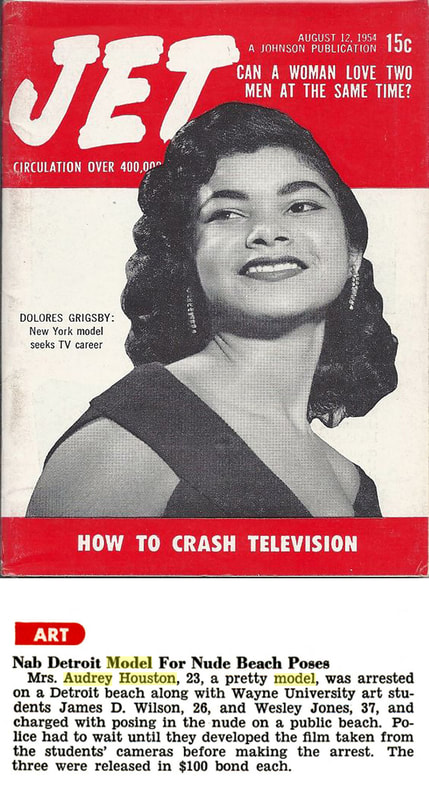

Artists' models have been posing for paintings and sculptures for thousands of years but rarely do we know who these models were. The Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum’s archives contain a few newspaper and magazine clippings that introduce us to one such model.

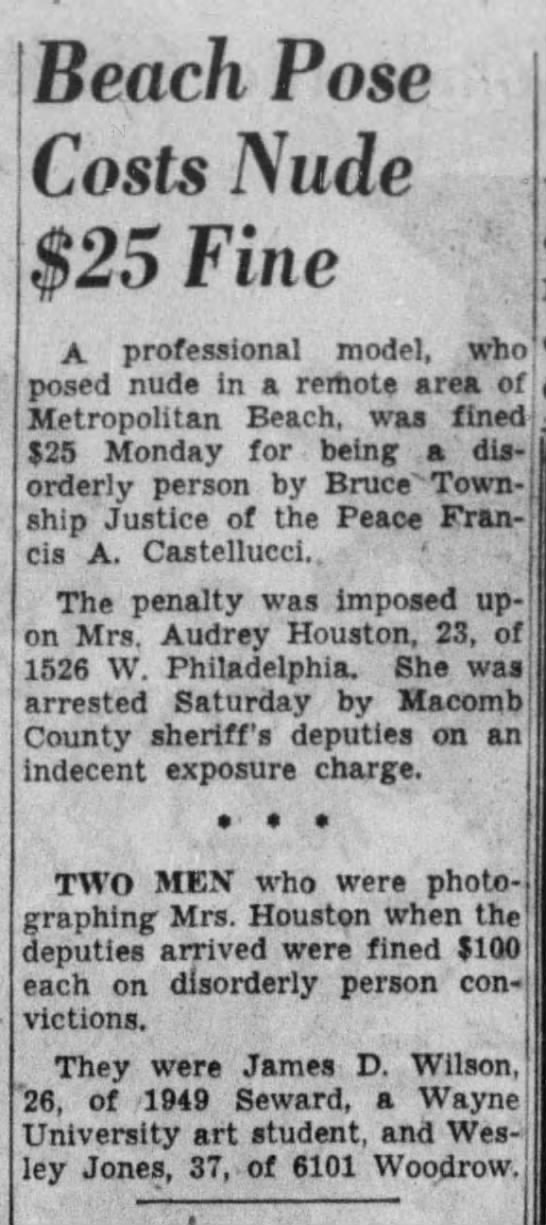

In a Detroit Free Press article on artists and their models, the popular Detroit-based artist Marshall Fredericks was featured along with one of his model’s, Audrey Houston. It appears that miss Houston was a favorite model of Fredericks known for her "pretty bones and muscles.” Miss Houston gained additional publicity in August 1954 after being arrested for posing nude on a Detroit beach. Click on the news clippings below to read more!

In a Detroit Free Press article on artists and their models, the popular Detroit-based artist Marshall Fredericks was featured along with one of his model’s, Audrey Houston. It appears that miss Houston was a favorite model of Fredericks known for her "pretty bones and muscles.” Miss Houston gained additional publicity in August 1954 after being arrested for posing nude on a Detroit beach. Click on the news clippings below to read more!

The Drawings of Marshall Fredericks By: Louis Marinaro, Sculptor

Like many visual artists Marshall Fredericks found it necessary, important and useful to draw. Drawing, the act of, is one of the unifying practices in the visual arts. Drawing is what commonly connects across disciplines. It allows visual artists to imagine, express and capture notions and ideas quickly. Ideas can be fleeting; drawing allows for quick responses to these ideas.

As evidenced in the works on exhibit, it is clear that Marshall Fredericks’s hand was always active and responsive to the marks on a page. On view in this drawing exhibition is a wide and varied set of works that are similar and different. Similar because they are made by the same artist. Different because the intention varies. At times drawing from models and at other times drawing portraits.

Marshall Fredericks approaches the task of drawing dependent upon his needs. At times, the drawing was a way of him clarifying an idea about form. At other times, it was a way of exploring new paths in his sculpture, and yet other times, a way of capturing a specific likeness of his sitter.

All of the works in this exhibition are works from life. Meaning that they are drawings from observation, not from memory. The mark-making exhibited in all the figure drawings from the live model are echoes of the forms in Marshall Fredericks’s sculpture. These drawings from the live model appear to be constructed as if in some solid stone-like material. Not unlike the three-dimensional work of the artist.

To understand these drawings, I will separate the works into three stylistic categories. These categories are not hard and fast, but I think they provide a useful way to understand Marshall Fredericks’s thinking related to these works.

Gesture drawings from live nude models (examples, 2000.617, 2000.621, 2000.628 and 2000.634)

These quick gesture drawings imply a rapid study showing a clear hand in capturing the gesture and position of the model. These gesture drawings are devices that artists use to focus and free the mind of outside distractions. To express as quickly as possible the insights of the artist and the relationship to the models form, pose and expression.

Sustained drawing studies from live nude models (examples, 2000.618, 2000.632 and 2000.637)

These are more nuanced works. Marshall Fredericks searches for just the right mark to suggest the ideas of his thinking. The marks in these drawings suggest a need to recall and record important details. The intention is to study the form and record gestures and feeling maybe to be used in the work of sculpture or just for the enjoyment and practice of meditating on the figure and its potential ideas.

Portrait drawings from life (examples, 2000.636 and 2000.638)

These are intended to capture the likeness of a particular individual. Both of these works express an understanding of figure structure and form on a deep level. These works are very focused and intended to define the individual’s character and demeanor. They express an insightful look into the complexity of life with regard to the individual presented. They represent Marshall Fredericks highly skilled craftsmanship and sensitivity as an artist.