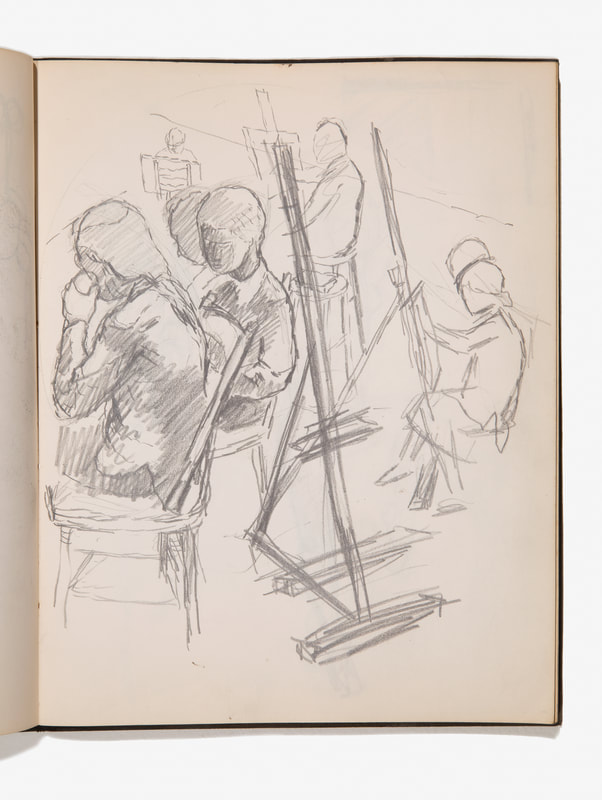

Artistic Training

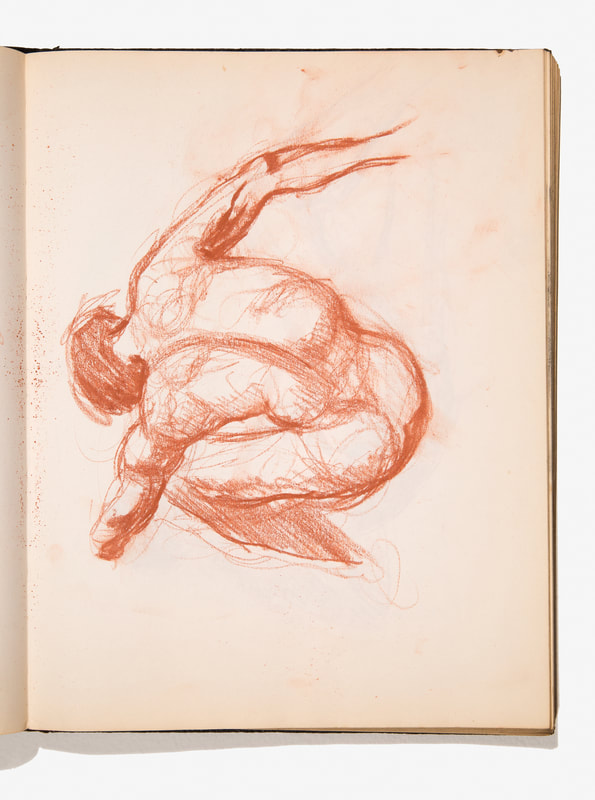

Harold Neal, Hughie Lee-Smith, Glanton Dowdell, LeRoy Foster, Henri King, and Charles McGee all studied at Detroit’s Society of Arts and Crafts (SAC, now College for Creative Studies). Unlike its competitor, Meinzinger’s art school, SAC welcomed African American students, many of whom, like Neal, paid their tuition with World War II’s GI bill. Training at SAC was grounded in life drawing.

Harold Neal, Hughie Lee-Smith, Glanton Dowdell, LeRoy Foster, Henri King, and Charles McGee all studied at Detroit’s Society of Arts and Crafts (SAC, now College for Creative Studies). Unlike its competitor, Meinzinger’s art school, SAC welcomed African American students, many of whom, like Neal, paid their tuition with World War II’s GI bill. Training at SAC was grounded in life drawing.

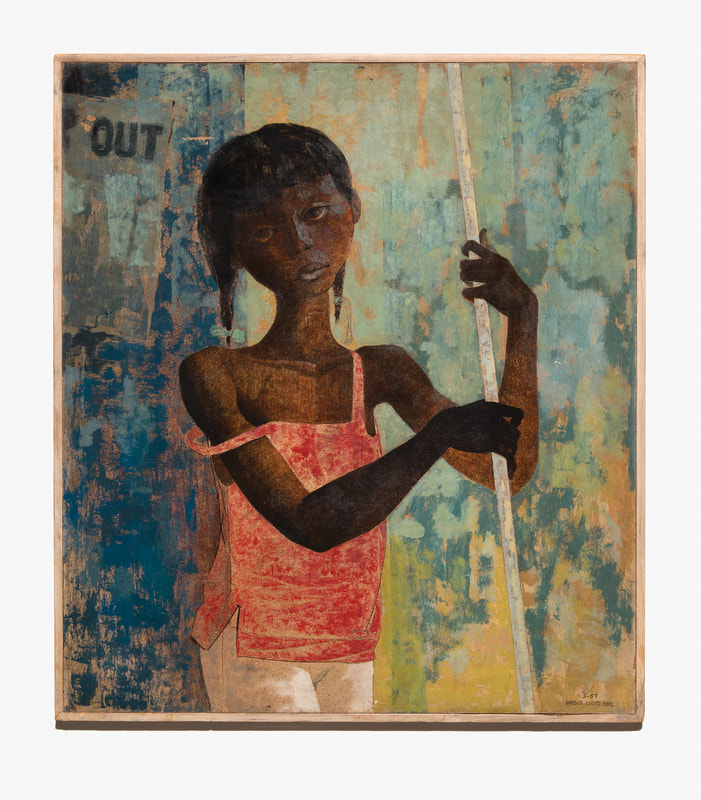

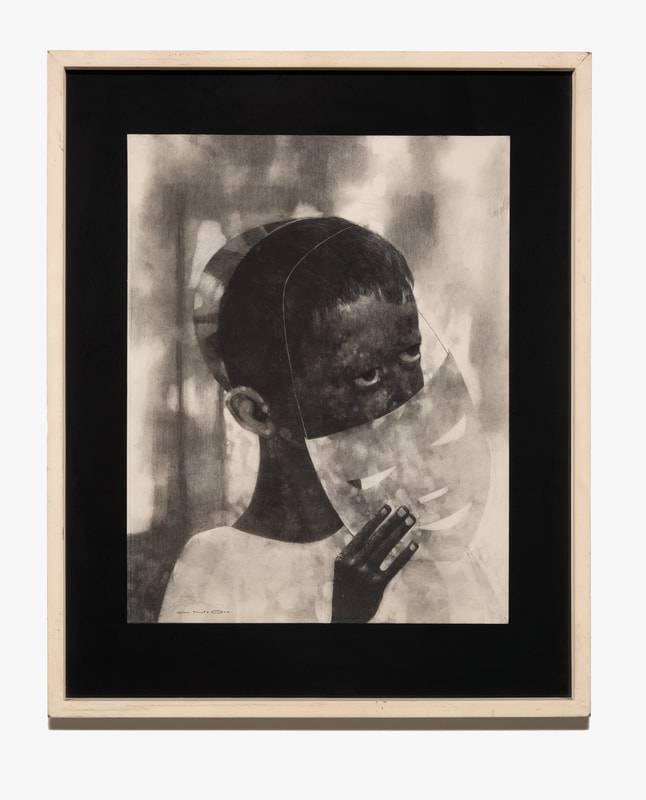

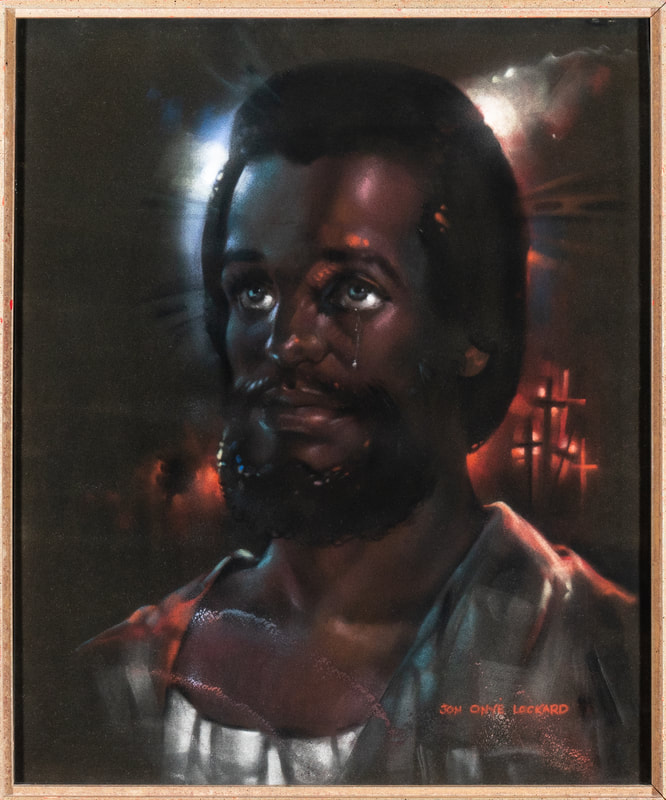

Neal was influenced by the surrealist style of Hughie Lee-Smith, such as his depiction of inexplicable poles and balloons in his image of young girl, 1957, and in his Status Seekers, 1963. Status Seekers and Neal’s painting of a man with a balance (at the beginning of the exhibition), as well as Charles McGee’s Mask, c. 1962 and Jon Lockard’s If I Were Jehovah (later in the exhibition) refer to Paul Laurence Dunbar’s c. 1895 poem “We Wear the Mask,” which poignantly describes the lives of Black people in America.

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,--

This debt we pay to human guile

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile

And mouth with myriad subtleties

Why should the world be over-wise,

In counting all our tears and sighs?

Nay, let them only see us, while

We wear the mask

We smile, but oh, great Christ, our cries

To thee from tortured souls arise.

We sing, but oh the clay is vile

Beneath our feet, and the long mile,

But let the world dream otherwise,

We wear the mask.

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,--

This debt we pay to human guile

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile

And mouth with myriad subtleties

Why should the world be over-wise,

In counting all our tears and sighs?

Nay, let them only see us, while

We wear the mask

We smile, but oh, great Christ, our cries

To thee from tortured souls arise.

We sing, but oh the clay is vile

Beneath our feet, and the long mile,

But let the world dream otherwise,

We wear the mask.

“Seeking Respite”

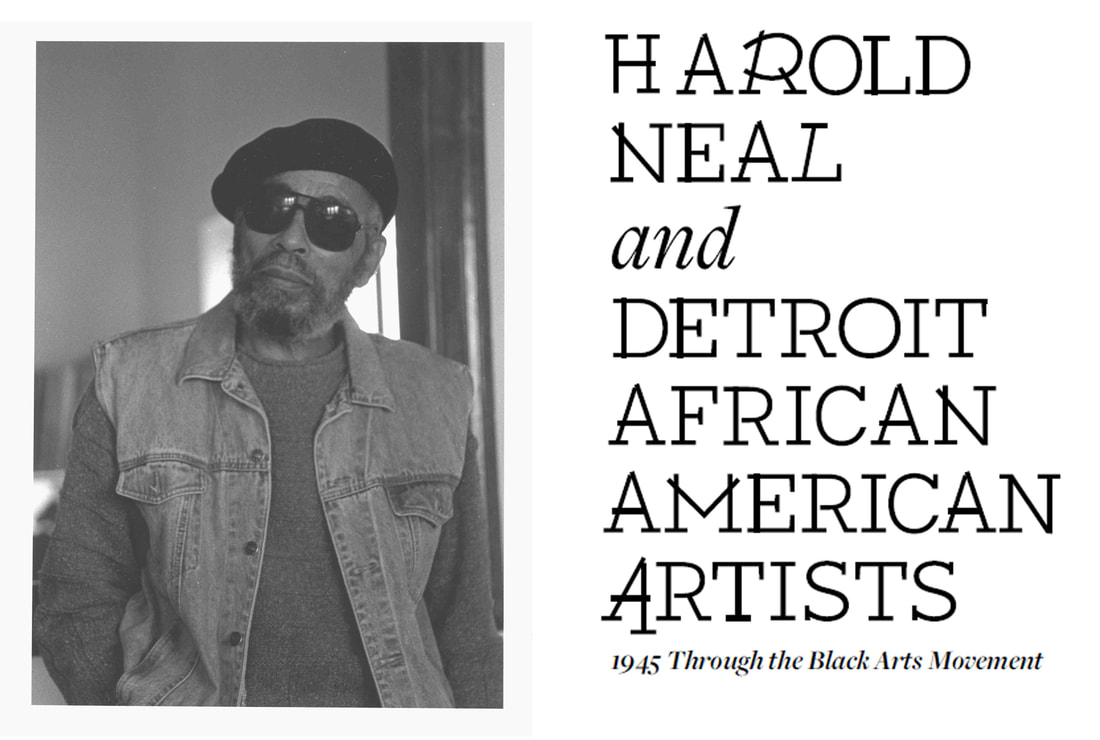

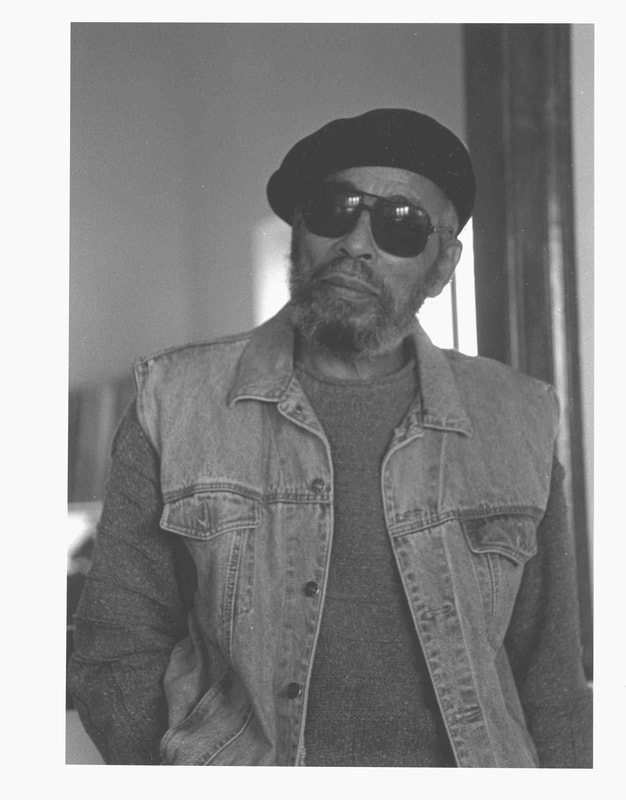

In 1969, at the height of the Black Liberation and Black Arts Movement, Neal wrote that “sometimes in seeking respite” from his anger about discrimination against African Americans, he “explored the beauty of Black women and children. Other times I try to show through paintings of bridges, houses and still life what the human hand is capable of in the brief period between its destructive endeavors.”

In 1969, at the height of the Black Liberation and Black Arts Movement, Neal wrote that “sometimes in seeking respite” from his anger about discrimination against African Americans, he “explored the beauty of Black women and children. Other times I try to show through paintings of bridges, houses and still life what the human hand is capable of in the brief period between its destructive endeavors.”

|

Radicalization: Black Nationalism

Harold Neal was sympathetic to Black Nationalism, which was advocated by Malcolm X. Unlike the integrationist approach of Martin Luther King, Jr., Black Nationalism held that, for the betterment of their people, African Americans should separate themselves from white society and develop their own economy and culture. In the mid-1960s Neal began to create more socially conscience works of art. Reluctant Flowering depicts a 13-year old girl, who, already a prostitute, has become pregnant. |

|

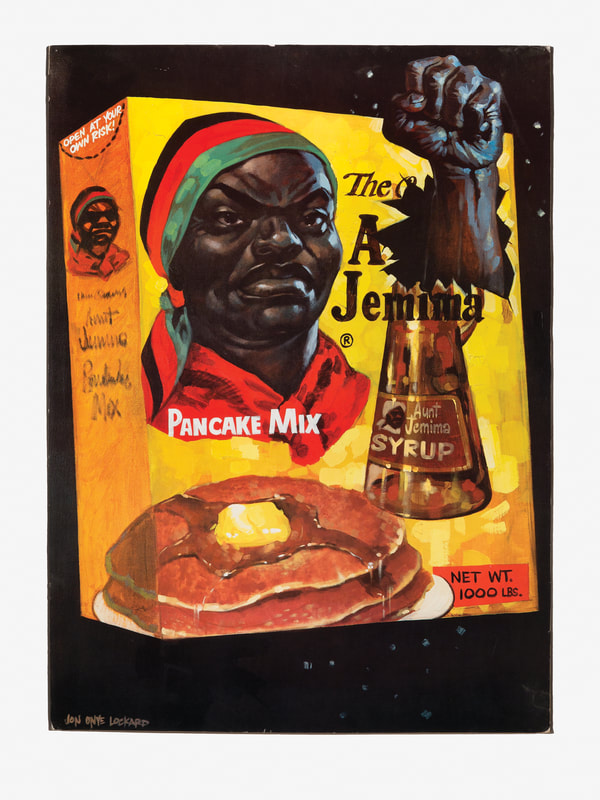

Radicalization: Black Christian Nationalism

Related to Black Nationalism was Black Christian Nationalism, which was led in Detroit by the charismatic Rev. Alfred Cleage, Jr., pastor of Central Congregational Church (later the Shrine of the Black Madonna). To Cleage, white Christianity was a tool of oppression. Neal, apparently, agreed. His painting of a man with a cross seems to depict a white Jesus bringing the chains of slavery to Blacks. This was, according to some interpretations, sanctioned by the Bible in Ephesians, VI, 5-7: Bonded “servants, be obedient to … your masters …as unto Christ.” Here revenge is sought by a black bird who is gouging out the eye of the white Christ. |

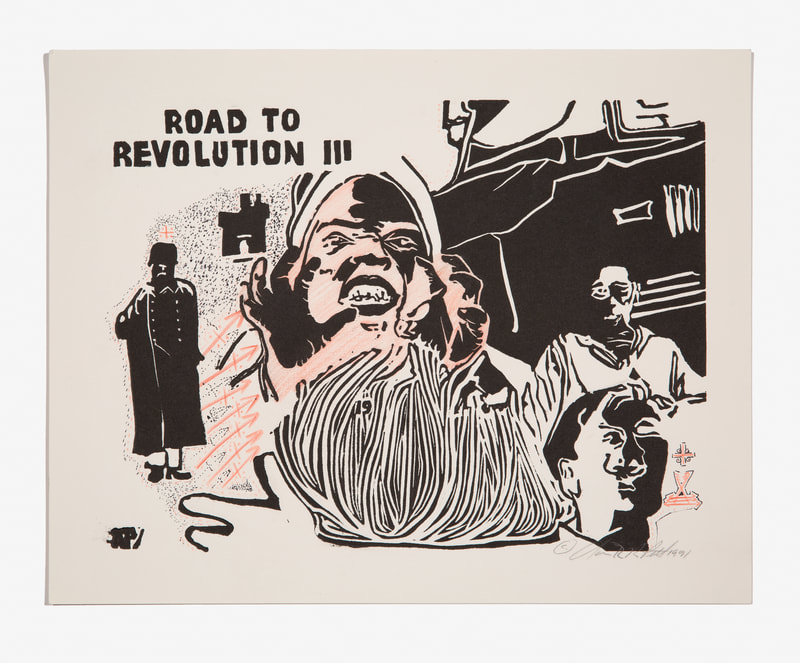

The Black Arts Movement in Detroit

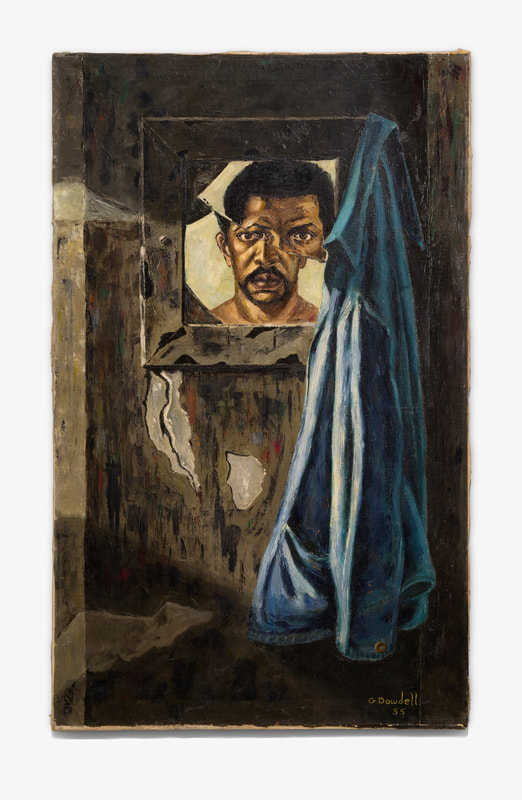

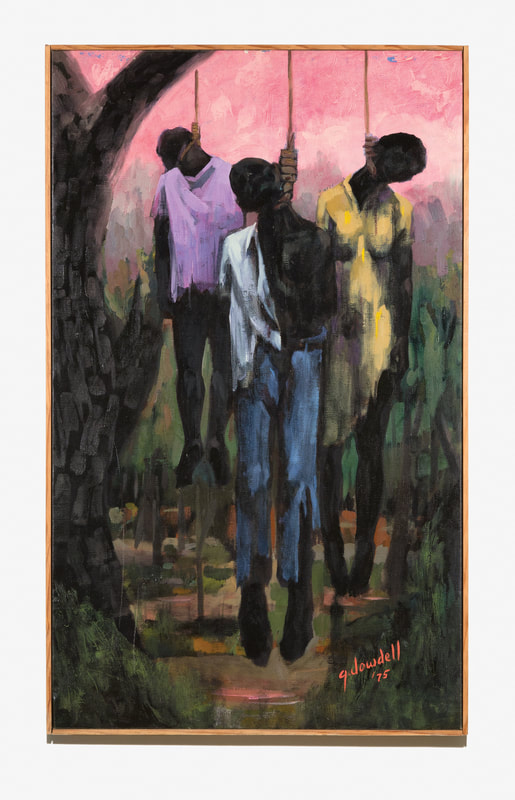

New York poet and playwright LeRoy Jones (later Amiri Baraka) started the Black Arts Movement (BAM) in 1965 following the assassination of Malcolm X. The BAM held that Black art should be about the African American experience, which, adherents felt, was categorically different from that of whites. These ideas premiered in Detroit in 1966 at First Black Arts Conference, organized by Rev. Cleage; bookseller and radical activist Edward Vaughn; and Neal’s friend Glanton Dowdell, who had been released from prison in 1962. The BAM was the artistic branch of the Black Power Movement, initiated in 1966 by Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) chair Stokely Carmichael.

On the visual arts panel of Detroit’s Second Black Arts Conference in 1967, Neal said:

Artists must stop being a specialist [sic] and must be like any other black man fighting for his freedom. … [I] don’t go along with tired white boys who introduce a series of dots one year and are hailed by critics who have to find something new.

Here Neal was referring to the abstract/non-objective art which then dominated the white art world.

In July 1967, shortly after the second conference, the Detroit uprising/rebellion took place and Neal responded.

New York poet and playwright LeRoy Jones (later Amiri Baraka) started the Black Arts Movement (BAM) in 1965 following the assassination of Malcolm X. The BAM held that Black art should be about the African American experience, which, adherents felt, was categorically different from that of whites. These ideas premiered in Detroit in 1966 at First Black Arts Conference, organized by Rev. Cleage; bookseller and radical activist Edward Vaughn; and Neal’s friend Glanton Dowdell, who had been released from prison in 1962. The BAM was the artistic branch of the Black Power Movement, initiated in 1966 by Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) chair Stokely Carmichael.

On the visual arts panel of Detroit’s Second Black Arts Conference in 1967, Neal said:

Artists must stop being a specialist [sic] and must be like any other black man fighting for his freedom. … [I] don’t go along with tired white boys who introduce a series of dots one year and are hailed by critics who have to find something new.

Here Neal was referring to the abstract/non-objective art which then dominated the white art world.

In July 1967, shortly after the second conference, the Detroit uprising/rebellion took place and Neal responded.

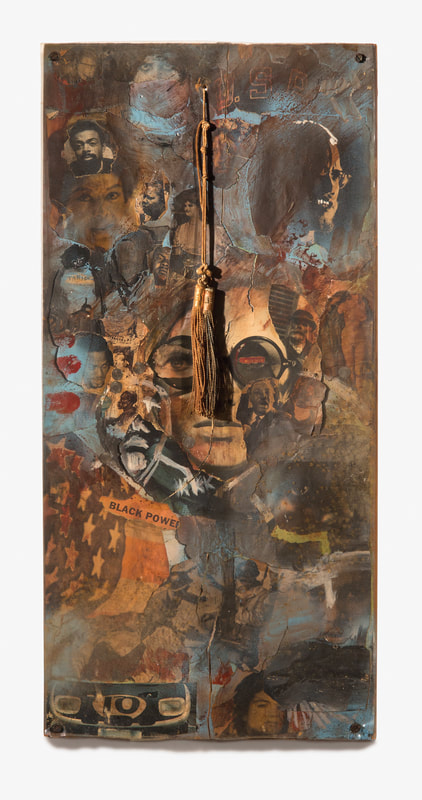

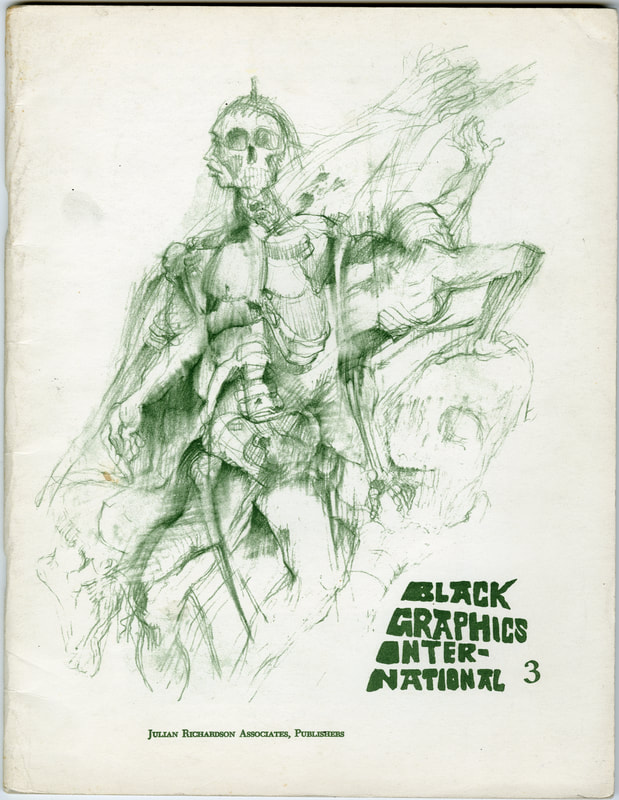

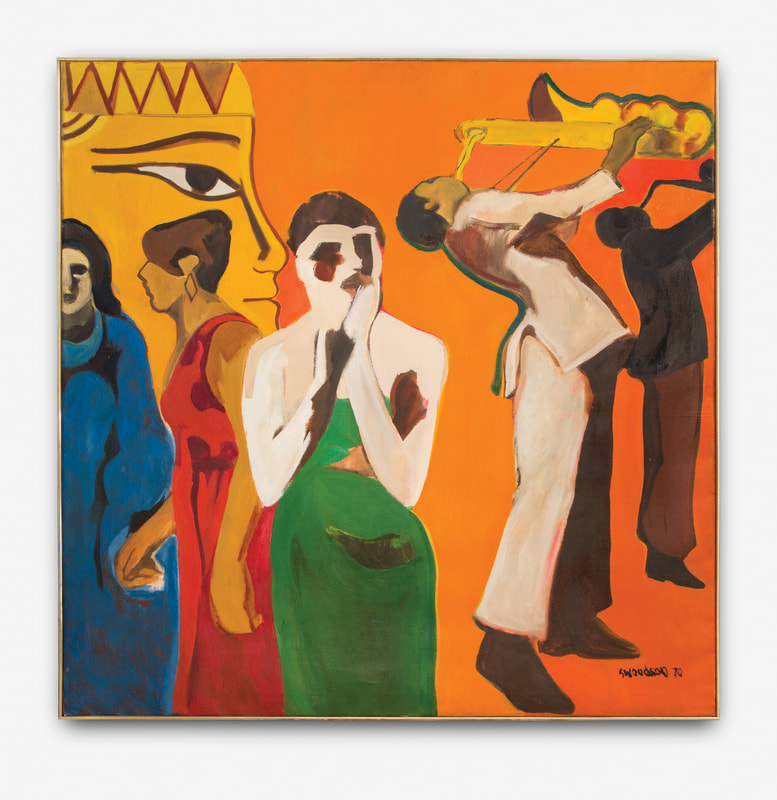

Other Black Arts Movement Detroiters

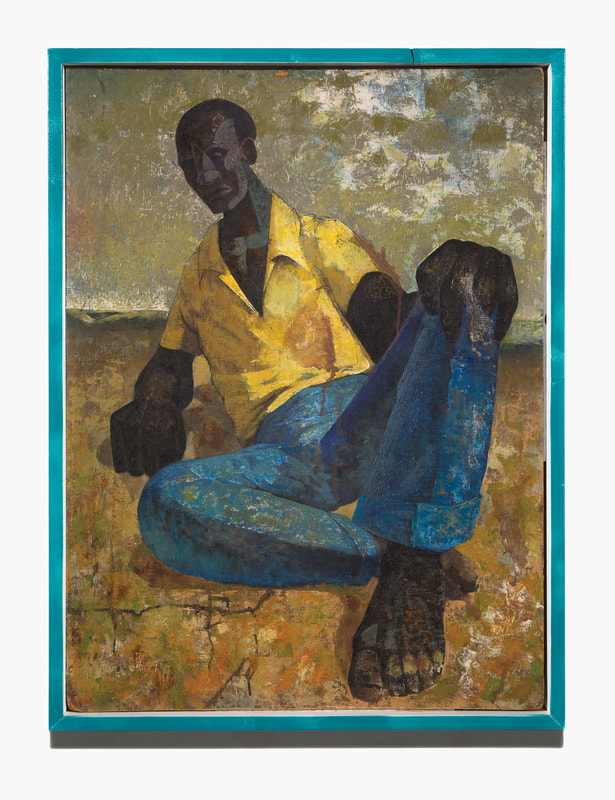

Like Neal, Jon Onye Lockard, Glanton Dowdell, and Neal’s younger friends, Aaron Ibn Pori Pitts and Allie McGhee asserted a Black Arts Movement agenda in their work.

Like Neal, Jon Onye Lockard, Glanton Dowdell, and Neal’s younger friends, Aaron Ibn Pori Pitts and Allie McGhee asserted a Black Arts Movement agenda in their work.

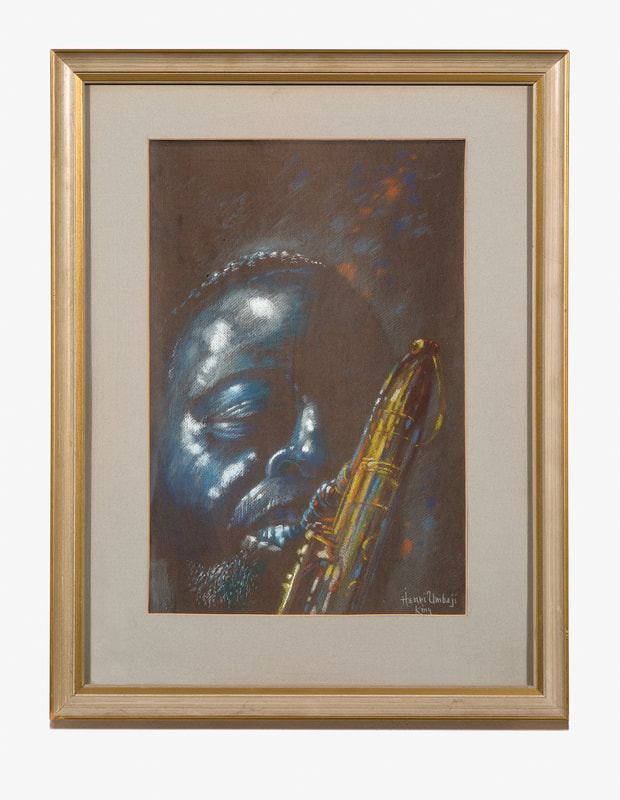

“Seeking Respite”—Reprise

Not all of the art created by Detroit’s Black Arts Movement artists was specifically political. This became increasingly true in the 1970s. Indeed in 1980, Neal wrote:

The more things change the more they stay the same. I don’t have time to be angry anymore. If you make me always direct my energy toward getting your foot off my neck, then you are oppressing me. … But I can’t carry the burdens of oppression on my shoulders my whole life.

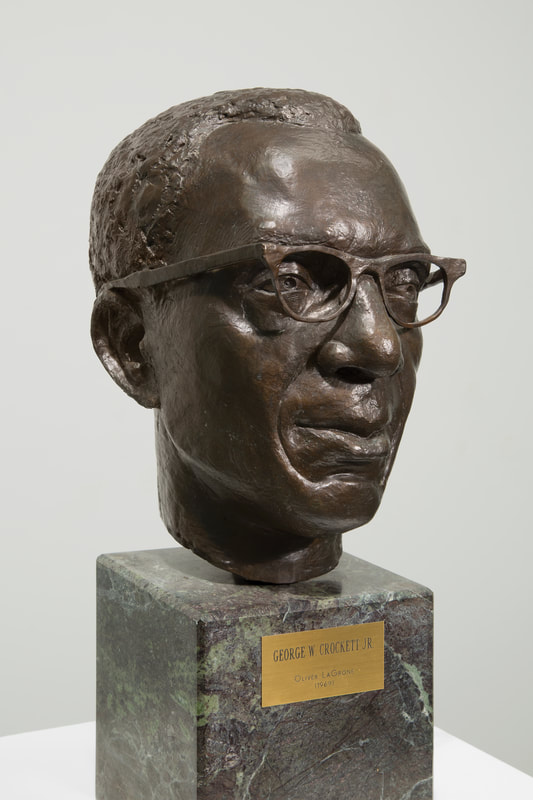

The BAM artists often focused on African American life, culture and heritage. They were particularly interested in portraying historical and contemporary American African heroes and sheroes, including public figures, musicians and actors, among others.

Not all of the art created by Detroit’s Black Arts Movement artists was specifically political. This became increasingly true in the 1970s. Indeed in 1980, Neal wrote:

The more things change the more they stay the same. I don’t have time to be angry anymore. If you make me always direct my energy toward getting your foot off my neck, then you are oppressing me. … But I can’t carry the burdens of oppression on my shoulders my whole life.

The BAM artists often focused on African American life, culture and heritage. They were particularly interested in portraying historical and contemporary American African heroes and sheroes, including public figures, musicians and actors, among others.

Conclusion

The 1980 election of Ronald Reagan marks the end of a revolutionary era in American life. Indeed, by the mid-1970s the fervor of the Black Nationalist, Black Power, and Black Arts Movement had begun to cool. There were many reasons for this, but in Detroit the 1973 election of Coleman Young, a former labor leader, a socialist, and a Civil Rights activist, gave new hope to Detroit’s Black community.

In the vernacular of the day, Harold Neal and the other artists represented in this exhibition “kept the faith, baby” with their community. Through their work of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, they protested the oppression of Black Americans and celebrated African American heritage, life, and culture.

The 1980 election of Ronald Reagan marks the end of a revolutionary era in American life. Indeed, by the mid-1970s the fervor of the Black Nationalist, Black Power, and Black Arts Movement had begun to cool. There were many reasons for this, but in Detroit the 1973 election of Coleman Young, a former labor leader, a socialist, and a Civil Rights activist, gave new hope to Detroit’s Black community.

In the vernacular of the day, Harold Neal and the other artists represented in this exhibition “kept the faith, baby” with their community. Through their work of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, they protested the oppression of Black Americans and celebrated African American heritage, life, and culture.

This Exhibition is made possible with the support of the Michigan Council for Arts & Cultural Affairs.